Sargent: Portraits of Artists & Friends

National Portrait Gallery, 12th February – 25th May 2015

There aren’t many painters whose works cause me to feel completely euphoric when I look at them, but Sargent is one of them. First and foremost a portraitist John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) was the most popular painter of his generation. A cosmopolitan and educated man his famous and cultured circle of friends provided a ready and willing subject matter. The NPG have got over seventy paintings on show here, and some rarely seen pencil sketches. Although I readily admit my total bias towards the artist, this is the best show I’ve seen in many years. Whether familiar with Sargent or ignorant of him I deplore you to visit.

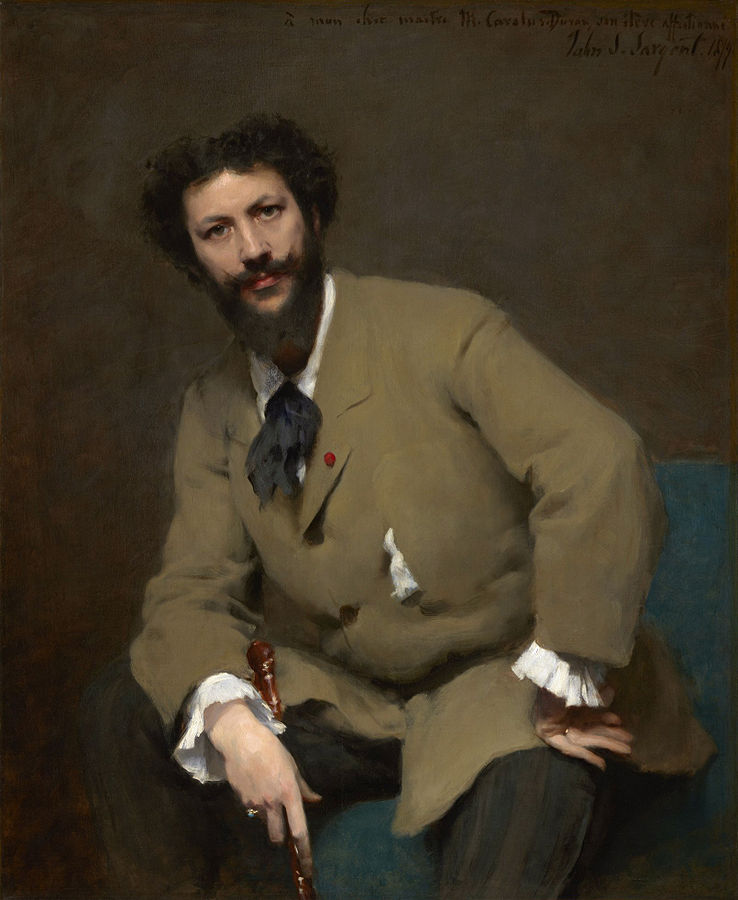

Sargent did not show a great deal of academic promise in his youth but he had a natural talent for drawing, and his mother who was an amateur painter herself nurtured it. His formal art education began in Rome at the age of 13, followed by a year at the Accademia in Florence in 1873. That year the family moved to Paris, the artistic capital of the world, where Sargent was accepted as an apprentice in the atelier of Carolus-Duran (Charles-Emile-Auguste Durant, 1838—1917). Sargent’s years with him were to prove defining ones. At the age of 23 Sargent painted his tutor. Carolus-Duran (1879), who at the time was a successful painter of high Parisian society. Sargent was Carolus-Duran’s star pupil, and he clearly admired his mentor. I think this intimate portrait is both a demonstration of Sargent’s well-learnt lessons under and a testament to their creative relationship. It is informal, not as staged as traditional portraiture, which gives it immediacy. He turns to face us in an open manner, there is a sense of honesty and mutual respect. It is not purely representational, there is a psychological element. I love the points of light which bring the painting to life; the glint in the eyes, the moistness of his lips, the polish of his cane and the glinting gold of his rings. If you take these away the painting loses something important. The face is the only thing that has been modelled with any realistic dimension. His clothes and the background are practically flat. The long-fingered hands are exquisite, something common in nearly all Sargent paintings. In these early years Sargent is establishing a visual language, later to become the artistic signature which makes him famous.

Portrait of Carolus-Duran (1879) by John Singer Sargent, oil on canvas, Clark Art Institute, Massachusetts

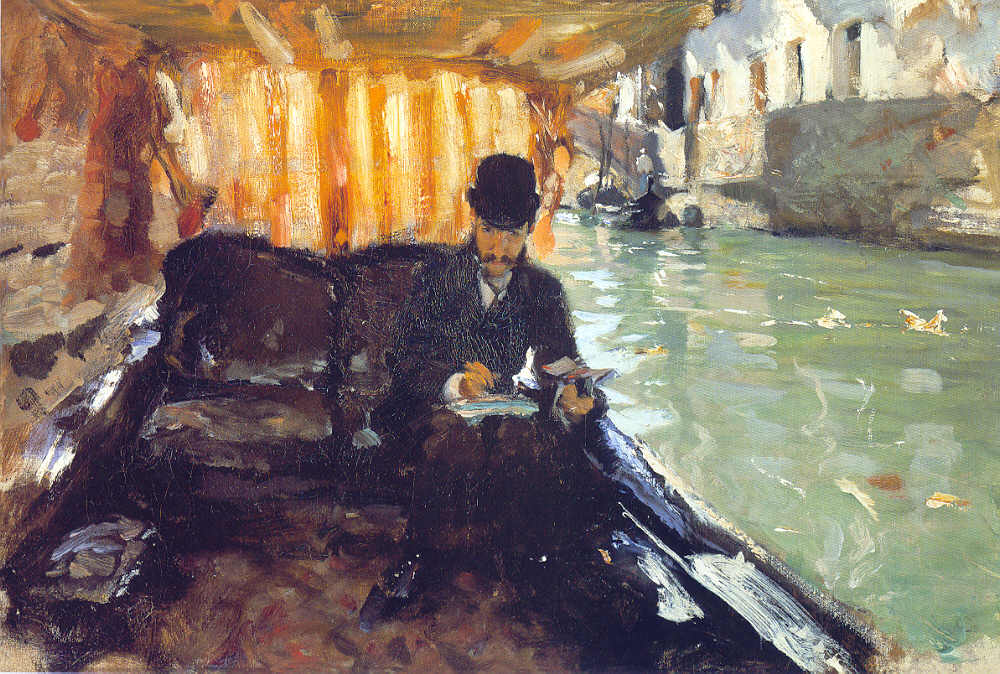

Ramón Subercaseaux in a Gondola (1880) caught my eye at once. Chilean politician and amateur painter Subercaseaux was a friend and staunch fan of Sargent, and this is the result of the two men painting each other while in Venice (unfortunately the counterpart is lost). The loose brushwork is beautiful, especially in the reflective canal water and the way the paint skips across the surface in squiggles. The strong sunlight coming through the awning of the gondola is wonderfully warm. Without being highly realistic it evokes Venice entirely. Although small in size and not a large finished canvas like his formal portraits it shows Sargent’s confidence and virtuosity as a painter. He has the innate ability to create dimension, texture and light through a few daubs or stripes of paint, however messily. Sargent knew the Impressionists (Monet was a friend) he did not associate his work with theirs. Although he must have been interested in what they were doing his own work remained idiosyncratic. The 19th century saw the development of the camera and the process of photography as we know it. Artists began looking at ways to depict the world in a way in which a camera could not. Sargent could have painted this scene with a high degree of realism, but he didn’t, and he creates something only he could.

Ramón Subercaseaux in a Gondola (1880) by John Singer Sargent, oil on canvas, Dixon Gallery, Tennessee

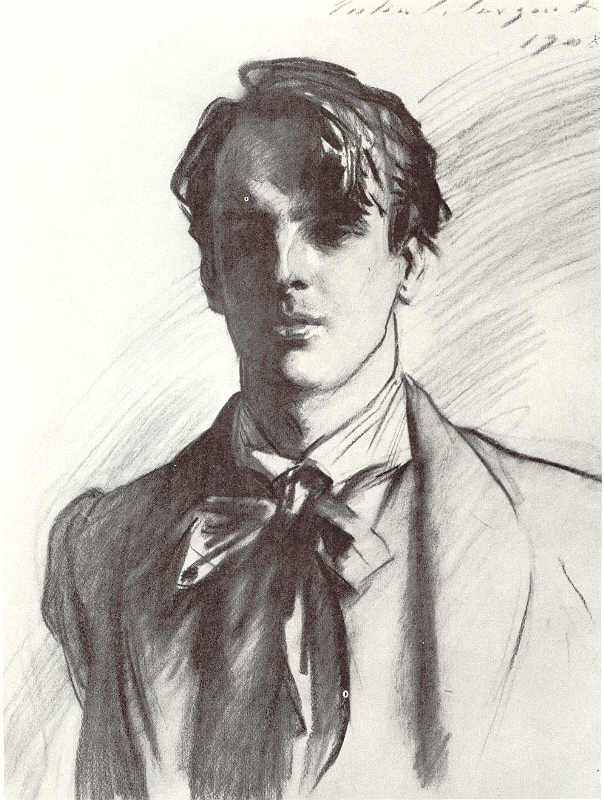

I had never seen any of Sargent’s drawings in the flesh so I must include one here. Irish poet and dramatist William Butler Yeats was a member of Sargent’s large intellectual and cultural coterie. From this sketch it is clear to see that Sargent drew the way he painted. The marks are so elegant and free, expressing a quickness and surety of hand. His finished painted portraits took on average eight sittings to complete, but apparently he always did the face in one. Here he captures the essence of Yeats. Photographs of him prove that Sargent was accurate in his depiction; the floppy mane, the distinctively shaped nose, and the set of the jaw are perfect. Sargent is described as a polite man, who made sittings relaxed and chatted to the sitter throughout. He painted straight onto canvas with no preparation, as Velazquez famously did. Sargent was a devotee of the Spanish master, travelling to Spain to study his works first-hand. This method is not forgiving of mistakes, and similarly here there is hardly a line out of place. Enviously it looks as though this drawing took a matter of seconds.

The inclusion of landscape in later works such as The Fountain (1907) shows Sargent’s love of painting en plein air. Here the subject is the fountain, but we only see a part of the basin and the jet of water spurting skywards. The foreground is dominated by a portrait of two people. They are Wilfrid and Jane Emmet de Glehn, both artists with whom Sargent travelled across Europe between 1905 and 1914. Jane is painting, her face turned from us with a look of concentration upon it, dressed all in white. Her husband reclines against the balcony of the pool, relaxed and content. It is a strange composition, all the action is over on the left-hand side. The couple are not sitting for the portrait, rather it is if Sargent has picked a single impromptu moment to depict them. Jane was very happy with the painting, writing to a friend that the image was the ‘spit’ of her, and that ‘Wilfrid is in short sleeves, very idle and good for nothing’. You can sense the relationships between the couple and the artist; natural and easy. Sargent travelled throughout his life, and the exploration of different places allowed him to experiment with his technique. This garden in Frascati has a wonderful clarity of air and sunlight, the effects of which can be seen most obviously on the water with thick impasto paint. The colours are beautiful, particularly in Jane’s smock. Upon closer inspection you can see dashes and daubs of yellows, oranges, greens, blues, browns and greys. The faces are quick strokes of a brush, minimal in detail. But from a distance the whole thing comes together in a symphony of colour. Sargent’s later years show an interest in landscape, and he made a habit of painting his various travelling companions, many of whom were artists themselves.

The Fountain, Villa Torlonia, Frascati (1907) by John Singer Sargent, oil on canvas, Institute of Art Chicago

John Singer Sargent is a painter of singular genius. Throughout his career he created around 900 oil paintings, 2000 watercolours, and countless sketches. Through his famous large portraits he achieved fame and wealth. I think what made him so popular is his innate ability to capture the essence of a person, as seen in paintings such as that of Carolus-Duran a glint an eye, a posture or a tellingly positioned hand can give an impression of an individual. However grand his canvasses he always retains subtlety and effortlessness, making it all about the sitter and their personality. The success and high demand that he experienced for most of his career meant that he had the freedom to pick and choose commissions and make time to pursue his own artistic interests. He was obviously a hardworking and dedicated artist, and even after the scandal of Madame X (1884) he was able to resume work and re-establish his reputation. Sargent didn’t have assistants, he mixed his own paints, prepared his own canvasses and dealt with sales himself. He earned around $5,000 per painting, which equates to about $130,000 in current currency. The status of those he painted gives his oeuvre a glamour which transfers onto his own life. Every wealthy society lady wanted to be immortalised by him. But, as I think this show demonstrates, it is his pictures of his beloved and esteemed friends which tell us most about the artist himself and shine brightest.