Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932

Royal Academy of Arts, London

11th February – 17th April 2017

This week I was incredibly fortunate to be invited to the private view of the RA’s latest blockbuster, Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932. I didn’t know what to expect, as my art history knowledge is shamefully limited to Western Art. I know of the obvious artists, Kandinksy, Malevich and Chagall. I have always found the country’s history and politics hard to get my head around, but I usually find that art and culture reflect what is going on at the place and time of its creation, and this exhibition proved to be a valuable lesson.

Revolution is a word that is inextricably linked to Russia. The 15 years covered by this exhibition reflects the civil unrest, power struggles and extreme social inequality. Like the views of the time, the exhibition is divided by art that hearkens back to Russia’s past (non-Western tradition, scenes of pastoral utopia and honest workers) and design that looks to the future (abstract images of machine-driven industry, uniformity and visions of political control). The latter avant-garde style leaked into graphic design, photography, film, furniture and decorative arts, and this take-over of all creative output shows the extreme reaches of the current affairs of the country and the preoccupation of it’s artists.

Dynamic Suprematism Supremus (c.1915) is a work that reacted to the revolution in Russia. Malevich founded the Suprematist movement in 1913 in order to find relevant ways to express pure ideas in art through colour and composition, “at once individual in a collective environment and individually independent”. He used tone and form in a way not dissimilar to grammar, and geometric shapes such as triangles, circles and squares were the foundation for this. Malevich stated that “Art no longer cares to serve the state and religion, it no longer wishes to illustrate the history of manners, it wants to have nothing further to do with the object, as such, and believes that it can exist, in and for itself”.

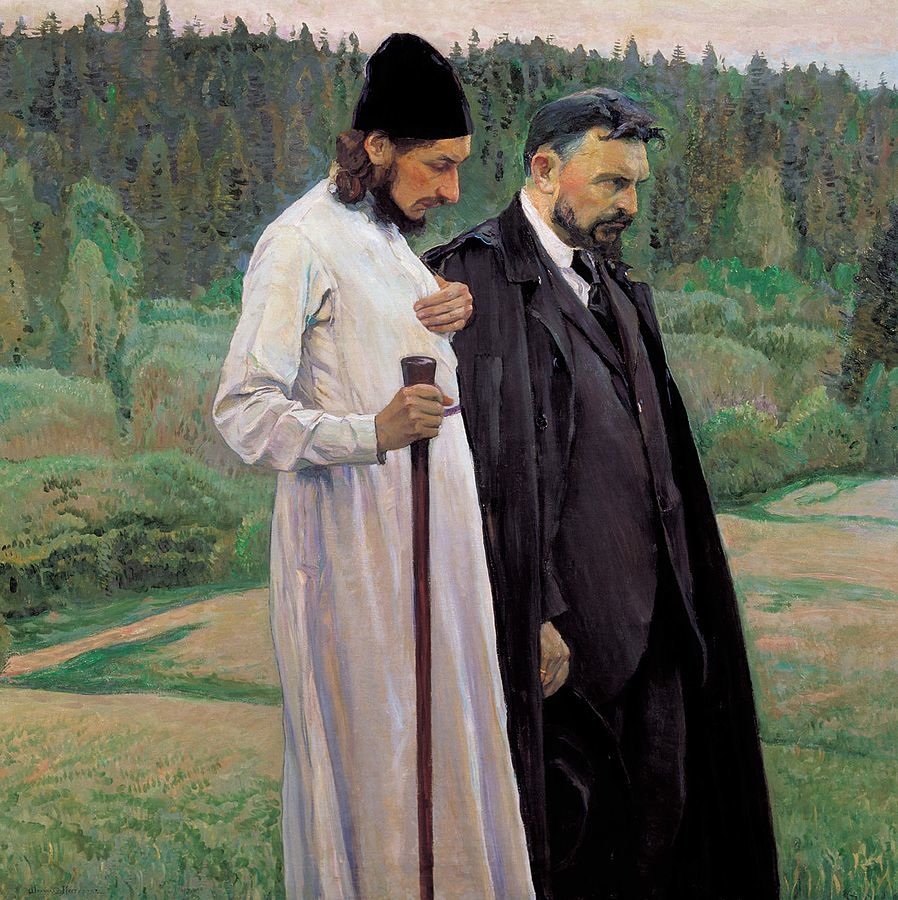

Philosophers (1917) by Mikhail Nesterov is a work that stood out to me in the show, not only because of how beautiful it is but also the story behind it. The two figures, Father Pavel Florensky, priest and polymath, and economist and theologian Sergei Bulgakov, both great Russian philosophers. Although the artist famously proclaimed “I’m no portraitist!” you can’t help but feel this painting gives us something of the two men’s characters. These two men, friends and allies in their thinking, stand in a Russian landscape as symbols of an awakening of conscience and moral upholding. I love the profile of the faces, the light and the textures, both rough and refined.

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin‘s Fantasy of 1925 represents a style of painting that reflects a truly Russian tradition. As a Soviet artist, Petrov-Vodkin paints with a spirit of radicalism, using what he called “spherical perspective” to portray his visions. He had trained with traditional icon painters, but the style he developed (along with his critical eye for Russian politics) became something completely individual. His work was often censored as blasphemous or erotic – opposing the Social Realism that was deemed appropriate by the State. But he was interested in communicating his own message; one of the essence of life. And so from the 1910s began to look to his homeland and its traditions for inspiration. As a professor at the Academy of Art he went on to inspire the next generation of Russian artists, and despite attempts to erase his name from Russian art history he is remembered as a revolutionary painter.

The 15 years spanned in this exhibition is of a country divided, a time of tumultuous revolution that was directly absorbed by the art and design that sprung from it. The radical social and political changes that were happening created a reaction through the emerging avant-garde artists that were looking for new ways to express themselves and their times. Some chose to reject tradition and history and invented their own style, others looked to the past to find new meaning and justification. Either way, the works on display here provide us with a history lesson, one that remains relevant 100 years on.