Raphael: The Drawings

The Ashmolean, Oxford

Until 3rd September 2017

Michelangelo wrote of Raphael in a letter “everything he knew about art he got from me”. Like his predecessor, Raphael was a master draughtsman, able to draw accurately and rapidly, but also with that rare ability of committing his thoughts to paper confidently, translating ideas into lines, defining and refining as he went. Michaelangelo also ‘doodled’ this way, but where Michelangelo was powerful and sculptural, Raphael was delicate and graceful. Michelangelo’s drawings usually show a direct route form an initial and finished design. Raphael was not only interested in the process, but revelled in that creative freedom and energy that is at the core of being an artist.

I have to start with the opening exhibit, Portrait of a Youth (self-portrait) dated around 1500-1. It really shows Raphael’s genius from a young age. If this is indeed a self-portrait, as it is widely believed to be, the artist is 17 years old. It is clear that the seed of what will grow to be Raphael’s enduring style is there in the confident but elegant lines. There is realistic weight, texture and vivacity there, created by modelled cross-hatching and smudging. Despite a reservedness in the boy’s eyes we can see that Raphael understands what a good portraitist can do for a sitter, revealing some personality but preserving some mystery.

Many of Raphael’s paintings and frescos are portraits or religious scenes, notably of the Madonna and Child. It was an important theme to the artist, and he returned to it continually throughout his life, reworking and revising the most holy of scenes, but yet the most ordinary. Raphael drew from life, and there are examples in the gallery of sketches of mothers holding babies. A seated mother embracing her child (c.1512), a tender and acute observation of maternal affection. The mother, posed on a chair, wraps her arm around the child, who stands on her gown in natural contrapposto with one arm raised. It has an immediacy about it, as though the child has just run over to tell its mother something in a very child-like way. I love how close their faces are, you can imagine the hushed tones as the child speaks and warmth between two of them. The mother’s drapery is depicted masterfully, with sure but subtle pencil marks and fluid zig-zags of white highlight, Raphael gives the illusion of solidity beneath and while creating a light silky texture with movement.

A seated mother embracing her child, c. 1512, metalpoint with white heightening on grey prepared paper, © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

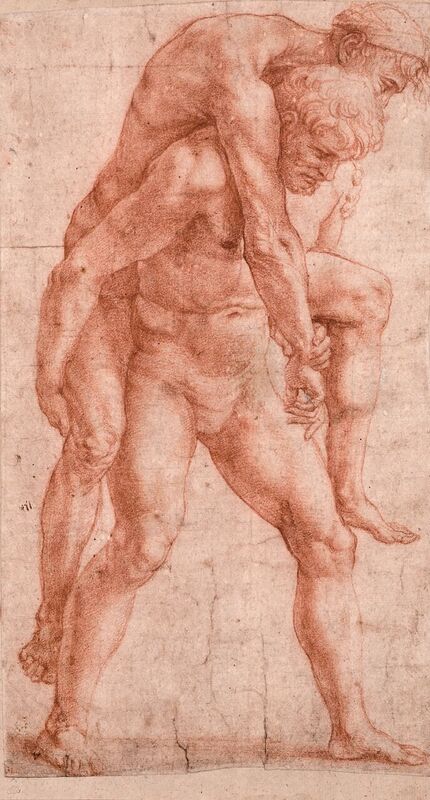

Like Michelangelo, Raphael used the male nude and knowledge of anatomy to portray emotion and create drama. And as Michelangelo, Raphael’s complete comprehension of the human body meant that he could experiment and create fresh compositions. We don’t need to see faces or expressions to understand this drawing; we can feel what Raphael is depicting from the way that he has done it. This is clearly a study from life, the way bodies intertwine and the muscles tense is so convincing and specific that they couldn’t be guessed or imagined. I love the way the men’s hands meet in the front, the younger wrapping his arm under the elder’s leg and getting a grasp on his opposite wrist. The contrast in the two bodies is wonderful, especially when looking at both of the men’s right knees. Although drawn just in red chalk, Raphael creates tactility through varying pressure of line and smudging, giving a realistic sense of living flesh.

When I think of Raphael’s paintings I think of the typical elegance and High-Renaissance grandeur. He possessed both of the desired qualities of an artist – colorito and disegno. But his drawings show a different side to him. There are 120 drawings on display at The Ashmolean, and although they can be grouped by theme, they show a relentless passion for experimenting through drawing. Drawing is more personal and intuitive than painting. It can more easily show personality in what is captured and how, revisions of thought and the processes of working things out spatially and anatomically. Raphael’s drawings show his love of certain repeated themes, but they are never the same. He had an agile and inventive approach to drawing which helped him to create finished masterpieces for the Pope and wealthy patrons. But his constant return to paper shows the core of his genius, that sprezzatura which is so vital to being a true master of art.