Painting with Light: Art & Photography from the Pre-Raphaelites to the Modern Age

Tate Britain, London

Until 25th September

Any show with Pre-Raphaelite or Impressionist works in are always popular, but can sometimes be a matter ‘style over substance’. This Tate show has done something unique, focusing on the very close relationship of photographers and artists, and their interchangeability. The two art forms – and we see how photography becomes a form of art in its own right – influenced and inspired one another, something that can be seen through some fantastic juxtapositions. The vast galleries were filled with treasures from the Tate collection and archives and enriched with some wonderful items.

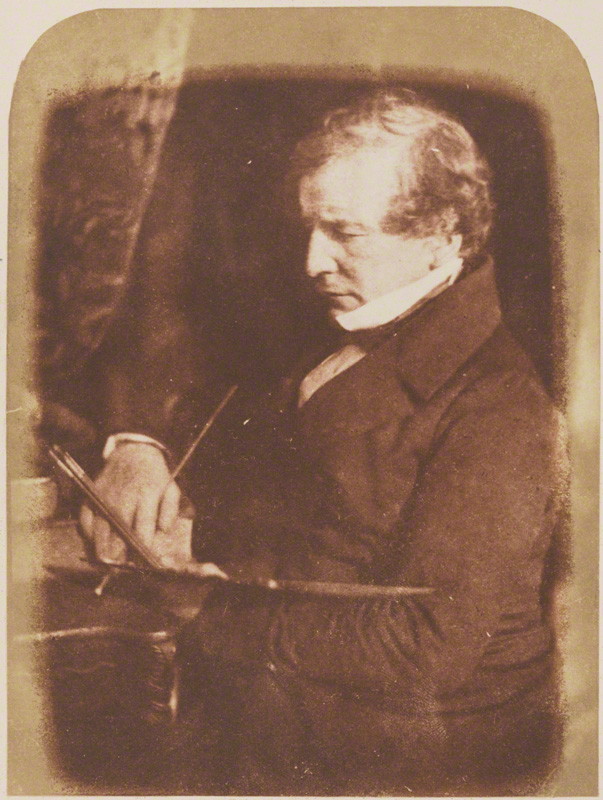

With the invention of photography in the 1830s, the rapid developments spread from the world of science into the world of art in a very natural way. Technological advances were enthusiastically paired with a creative interest from practising artists. Indeed some of the first famous photographers had initially trained as artists. The overlapping parallels of both industries become obvious from the very start. Something else that is obvious (that I hadn’t thought about before) was that photography allowed the artist to paint themselves without a mirror. The photograph of William Etty by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson was used to create a self-portrait in oil paint. A photograph allowed a completely new view on the self, as well as expressing something wholly about observation and reflection. The ethos of ‘reject nothing, select nothing’ was more relevant than with painting, as ‘the camera does not lie’.Etty said of the photo that it was a revival of Old Masters such as Rembrandt and Titian. Artworks could be photographed and circulated, increasing its exposure, and subsequently create a new hobby for collecting prints, one which Queen Victoria took up fervently.

William Etty (1884) by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, calotype, © National Portrait Gallery, London

Self Portrait after a photograph by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson (1844) by William Etty, oil on millboard, © National Portrait Gallery, London

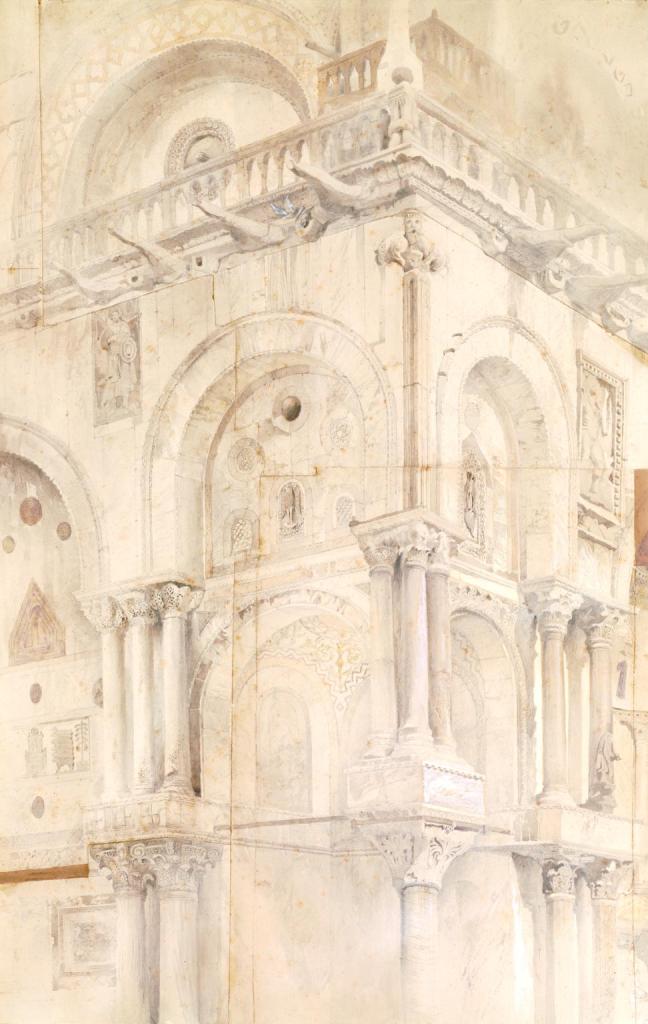

The rapid growth of photography made it more accessible, science found more effective methods and the equipment required became less cumbersome. It spread to the local high street, where families could have portraits taken, and eventually it became a hobby for ordinary people. Julia Margaret Cameron started taking photos when she was given a camera as a gift. Even John Ruskin, staunch defender of nature and craft in art, was an advocate of photography, finding that it allowed him to achieve a higher degree of truth and accuracy, as seen in his depiction of The North-West Angle of the Facade of St Mark’s, Venice (1819-1900). Ruskin owned hundreds of Daguerreotypes, including one of the exact view this drawing, explaining that ‘every chip of stone and stain is there, and of course there is no mistake about proportions’. I had never seen an original plate, and John Hobb’s mirror-like plate is beautiful, a ghostly reflection of watery Venice.

The North-West Angle of the Facade of St Mark’s, Venice (1819-1900) by John Ruskin, watercolour and graphite on paper, Tate, London

The North-West Angle of the Facade of St Mark’s, Venice (c.1850–1852) by John Hobbs, daguerreotype, Ruskin Foundation (Ruskin Library, Lancaster University)

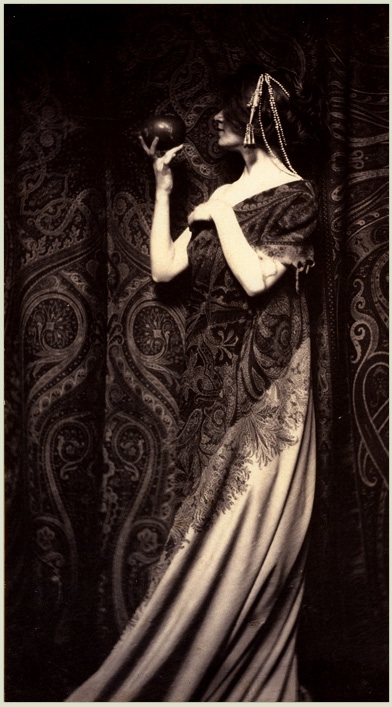

Another benefit of using photographs to compose an oil painting is getting the style and aesthetic right. Models could be frozen in a pose without hours of individual sittings, allowing the artist to focus on the overall work. Dante Gabriel Rossetti‘s muse and great love, Jane Morris, was photographed extensively. The exhibition even shows a photograph of Morris that Rossetti had ‘composed’ again emphasising the collaborative spirit of painters and photographers. I love The Odor of Pomegranates (1899) by Zaida Ben-Yusuf. It is so evocative of a far away land and a past age, but somehow it feels modern. It isn’t about the woman, or even really the pomegranate. It expresses form in a way that has been designed and orchestrated. The folds of drapery have been composed, the way the backdrop blends into the foreground and the level of contrast between the white of the sitter’s skin and the fade to black at the top and bottom of the photograph have been considered. In comparison to Rossetti‘s Proserpine (1874) we can see the influence of aestheticism, an exploration into the pleasure and sensuality of art.

From the pages of notes that I made as I went around this wonderful exhibition I have chosen just a few works to write about. The amount of information, both visual and information-based, is explored in such depth here. Many other topics were covered, namely landscape and tableaux. The extent to which painting and photography overlapped was a complete revelation to me. By taking a photograph an artist could freeze a scene, capture something transient or gain a new perspective. It could be used to depict a sublime landscape, like in Glacier of Rosenlaui by John Brett (1856), painting rocky surfaces and plumes of fog in a hyper-real way. Fleeting emotions or gestures that only a camera can see, caught perfectly in a portrait of Lady Ottoline Morrell (c.1907) by Adolf de Meyer become reference material for artists. And similarly, atmospheric effect and meteorological interests were explored in Gustave Le Gray‘s Cloudy Sky – Mediterranean Sea (1857), which is literally painting with light. Art and science were inextricably linked, feeding into one another and spreading inspiration globally.

In a world of ‘selfies’, instant photo-taking and millions of images just waiting to be scrolled through, we are desensitised by seeing things that mean nothing. Getting back to a time when photography required talent, technique and had meaning was a thought-provoking and visually refreshing experience.