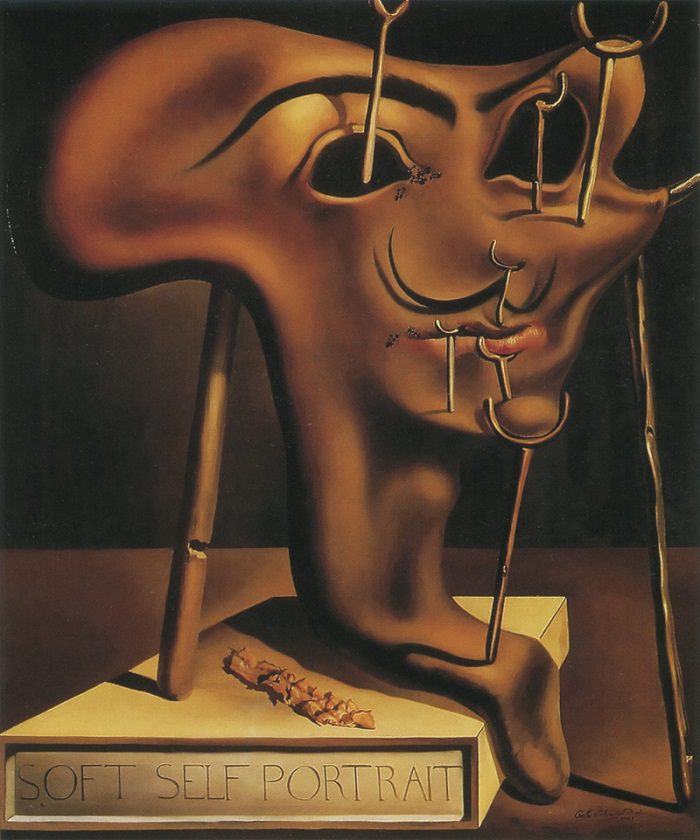

Soft Self-Portrait with Fried Bacon

You may find it surprising to know that Salvador Dalí was my first favourite artist. I remember discovering at him when I was studying GCSE Art & Design, and feeling that his paintings had something to say to me – perhaps disconcerting for a 15 year old. Looking back, I think the main appeal was his ‘painted dream photographs’, as I have always suffered from strange and often quite disturbing nightmares. I found the weird and macabre works of Dalí both compelling and comforting. When it came to studying self-portraits I returned to Dalí for inspiration because I felt that to depict myself accurately I could not paint my reflection in a mirror, but what I saw in it; sensation over reality. It was this painting, Soft Self-Portrait with Fried Bacon, that I became obsessed with after visiting the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres on a school trip and it has remained one of my favourite self-portraits.

Dalí’s eccentric, outspoken and larger-than-life personality extended beyond the celebrity art world, and I think it could sometimes overshadow his artistic genius. There is a lot of material out there in the way of interviews and psycho-analytical essays that attempt to encapsulate him and his work, try to get to the essence of the man behind the myth – much of which was concocted by Dalí himself. His most famous quotes include “each morning when I awake, I experience again a supreme pleasure: that of being Salvador Dalí”. Megalomaniac and provocateur are words associated with him, which when paired with his extreme appearance (his trademark moustache and flamboyant fashion sense) creates a caricature, untouchable on a human level. This is how he interacted with the world around him, but a self-portrait is an opportunity to say a lot more with honesty and without a facade, in this case quite literally.

The painting can be looked at on a basic level, without getting too deep into ideas and theories. As a Surrealist Dalí blurred the line between reality and imaginary in an often dark and haunting manner, exploring the psychological discoveries of the time (Freud in particular) but also harkening back to the irrational and emotive qualities of Romanticism. Creating art could unlock the subconscious mind, allowing us to experience and explore our true selves in an unrestricted way. He wrote that “to the outside world I assumed more and more the appearance of a fortress, within myself I could continue to grow old in the soft, and in the super-soft.” At its most simplistic this is a painting of an outer appearance, a mask or flayed face. Dalí presents it to us an object to be revered and studied, it is an artefact on a plinth. It could also be seen as a trophy, a memento of a victorious quest that immortalises the artist. Upon its stone base the title has been inscribed in an authoritative font. It is a trompe l’oeil of a self-portrait, but it isn’t about the artist’s technical ability, it is about transcribing something deeper through paint on canvas.

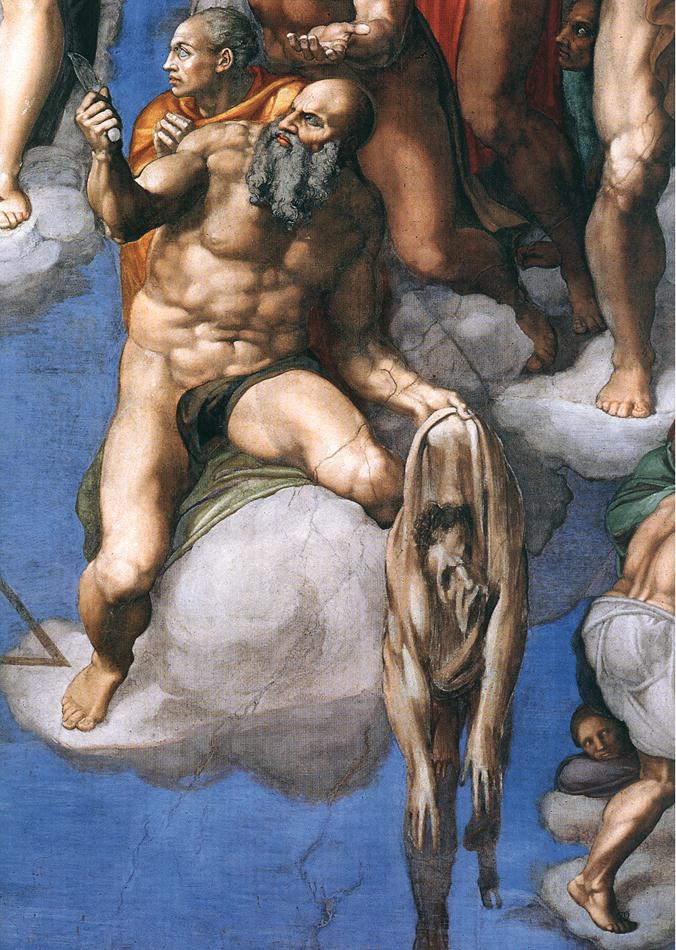

In the absence of eyes (often described as the windows to the soul), a recognisable facial expression, a posed body with clothes and adornments set against a backdrop, we may feel that we have little to read in terms of traditional visual information. Or perhaps we can feel undistracted so that we may reach another dimension of understanding. There are a few symbols though; ants, bacon, and crutches – objects that reoccur in his work. The ants that are crawling into the tear duct represent death and decay. On one hand bacon can represent food and sustenance, while on the other a slice of a dead animal flesh which will rot. Its crisp and undulating texture contrasts with the softness of the mask, making it look all the more flaccid and fragile. The crutches suggest weakness or vulnerability, without them the face would become a featureless liquid pile. It is said that Michelangelo painted his face on the flayed skin of St Bartholomew in the Sistine Chapel’s Last Judgement (1536-41), casting-off his inconsequential, mortal body to attain redemption through a pure, inner state. Perhaps there is something of this notion in Dalí’s self-representation. Both artists had arrogant and melancholy aspects to their personalities, both give insights into the psychological and the erotic through their art. Michelangelo’s contemporary biographer Asciano Condivi called him as bizzarro e fantastico, a description that could very easily be applied to Dalí.

The overriding thing this painting says to me is that this famous moustachioed face was just a veneer, something that Dalí hung up when out of the public eye. Something mortal that would die with him. He described it as “the glove of myself” and denied any psychological content – in fact he called it anti-psychological. But it is interesting that as a painter who continually painted his thoughts, fears, fantasies, and dreams openly, that when it came to a self-portrait we are denied a psychological reading of a man with a brain that was so interesting. While the physical ‘self’ is exposed the inner ‘self’ will always be somewhat private, and a self-portrait cannot tell us the half of what a person is really about at their core. Most of the time we do not fully know ourselves, and even if we did how could that be translated into a painting. Faces are rarely transparent, and no-one knows what is going on behind surface of the most composed and controlled self-portraits in art history. Yet we can relate to this elusiveness, and I find that a consolation.

I am reminded of a wonderful quote by the Argentinian writer and poet Jorge Luis Borges:

“I saw all the mirrors on earth and none of them reflected me”