Imprisoned Spring

We humans are connected to the natural world in a profound and innate way. We often seek to synchronise our bodies with the rising and retiring of the sun, we bask in its light and warmth, we crave fresh air and find joy in the sights, sounds and sensations of being outside. This month Winter officially turned to Spring, bringing with it longer, brighter days and more temperate weather. And yet while the COVID-19-induced lockdown is confining us to our homes, by maximising our significantly lessened experiences of nature (whether from indoors or out) and find a newfound gratitude for Springtime.

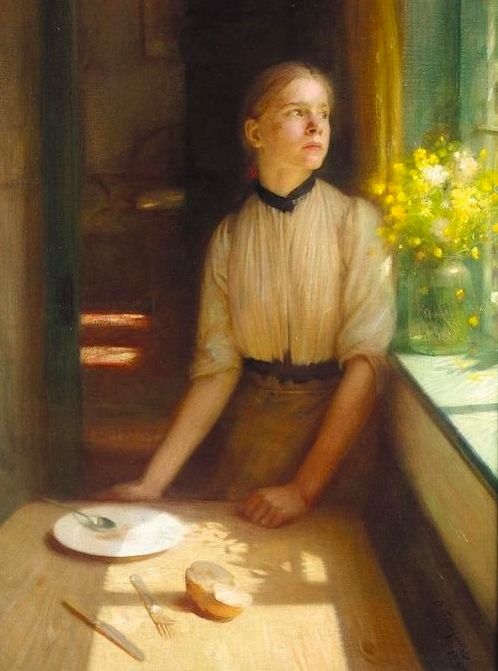

I have a little table set up by a window, where I read, write and work on jigsaw puzzles (my new obsession). Light floods through it around noon and on a clear day I have far-reaching views of the Surrey Hills, offering a welcome break for the eyes and mind from whatever I am doing. This seemingly modest painting, Imprisoned Spring (1911) by the British painter Arthur Hacker (1858 – 1919) captures a moment of distraction, offering us as a viewer a chance to observe a person looking out from the inside.

A simply dressed young girl, aproned and sleeves rolled up, has paused to gaze out of a window. Bright sunlight streams in, hitting a table in the foreground and the floor of the room beyond. On the table is half a bread roll, an empty plate and disregarded cutlery. It is unclear whether the girl has just eaten, or if she is about to clear away the remnants of someone else’s meal. On a green windowsill at her elbow, we see the edge of the window frame, the panes of glass just out of view. We are refused a view of the outside world and denied seeing what has caught the girl’s attention. A vase of white and bright yellow flowers sits between the girl and the window, perhaps a suggestion of what is beyond the canvas edge. While the loose style of painting does not describe the plants accurately enough to allow for identification, they are suggestive of wildflowers, such as cow parsley, daisies, buttercups and cowslips. The humble arrangement could suggest a rural household, or at least one surrounded by countryside.

The simplicity of the scene, the natural colours used and the lack of ornamentation in the interior allow us to focus on the girl and what she is experiencing. Perhaps she is staring into space, thinking about what she is about to do – very common and human behaviour. Perhaps she is watching birds in a tree, listening to their song and quietly considering their vitality. Or perhaps she feels a deep inner sense of her own existence, one which is at odds with the outside world. I think we need not worry about any meaning that the artist might have meant to impart here. The ambiguity invites us to think for ourselves, to flit between the role of the onlooker and participating in the girl’s experience. The complex relationship between inner and outer is what strikes me when looking at this painting, whether in relation to occupying a room looking out or inhabiting the self and contemplating the barriers and limitations of being human. Yet we can experience a strange phenomenon when we are in nature; we can feel ‘at one’ with it, free and unconstrained.

In one of my favourite art books, Art as Therapy by Alain de Botton and John Armstrong, the authors say that ‘[w]e have psychological frailties connected with looking at nature. Nature itself is not articulate about its powers, while we are unable to isolate its best parts and do not always accept the significance of the experiences we have in its presence.’[1] Art can help us reconnect with what nature means to us, inspire us to take the opportunity to seek out meaningful encounters with nature, and appreciate its awesome power, whether through a window or a canvas.

[1] De Botton, Alain & Armstrong, John. Art as Therapy. 2016. London: Phaidon Press. p.124