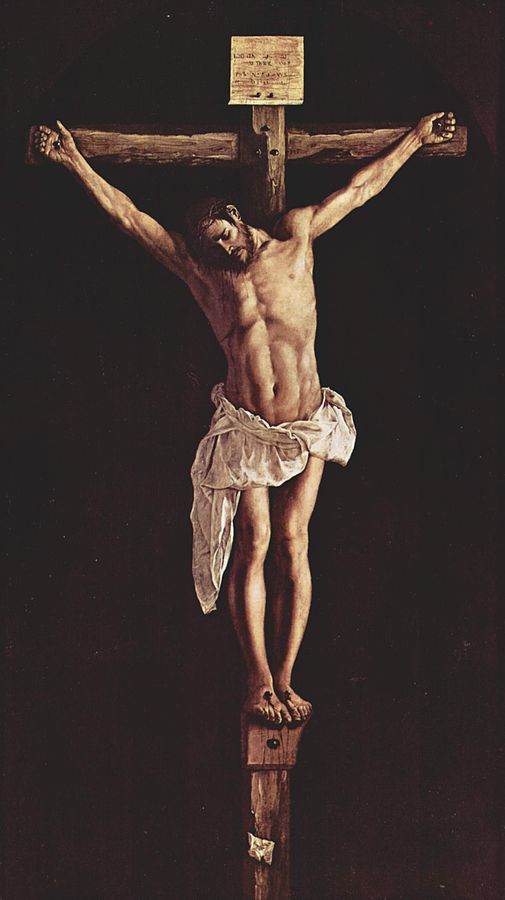

Crucifixion

Seventeenth-century Spanish Catholic art has a distinct visual language, reflecting the traditions of religious theory and practice in that specific time and place. While Protestantism enforced the biblical commandment forbidding the creation of ‘graven images’, the Catholic Church both defended and promoted their use of art to inspire piety and strengthen faith. As one of the most influential contributors to Counter-Reformation art in Spain, Francisco de Zurbarán mastered an emotive and psychological style of painting, particularly powerful in images of single figures like this Crucifixion, painted in 1627. Far from being sacrilegious, paintings such as were meant to be used as a contemplative aid, almost to be looked through rather than actually worshipped as an object itself. The artistic focus is on spiritual inspiration rather than instructive doctrine, and at the heart of it is a message about the individual encounter with God; the utmost aim of the sensory and meditative experience of Spanish Catholic ritual. As well as being a court artist Zurbarán fulfilled many commissions for the ever-multiplying monasteries, earning him the nickname ‘painter of monks’. This painting was done for the Dominicans, the medieval order whose confraternities were dedicated to lives of preaching, asceticism and solitude.

Although a visually simple painting this Crucifixion is very elegant and intelligent, a testament to the artist’s understanding of its purpose and place. With this in mind, I want to start with a basic formal analysis of what we can see, then go onto discuss what we can think about on a deeper level when looking at this masterpiece.

First and foremost, we are directly presented with a vision of Christ on the cross, the iconographic symbol of Christianity. As a viewer, we know what it represents and how we are supposed to respond to it – with pity, sorrow, compassion, and veneration. But it is not set in a landscape or against a heavenly gold background, as we are used to seeing the subject of the crucifixion in art. Instead, the crucified Jesus is submerged in darkness. It is also notable that there are no people included, none of the familiar biblical figures usually depicted at the scene. We alone are bearing witness, forced to confront the subject face-on and left with nowhere to hide or find distraction. It is reminiscent of the revolutionary paintings of Caravaggio that push us the subject out towards us and surround all but the necessary details in shadow. Zurbarán would have seen works by him and those he influenced in the art collection of his patron King Philip IV. But this composition is minimal in the extreme, and deeply rooted in Spain’s history of religious mystics and ecstatics – notably Saint Teresa of Ávila. She believed in the power of mental prayer and severe personal atonement as a necessary requirement of being united with God, and as a result of her spiritual focus and self-transcendence she received visions and ecstasies. The contrast between the corporeal realism of Christ’s body and the blackish void of the unknown in which we find ourselves could be seen as an invitation to follow this practice, so that we may be set upon the path of being blessed with such experiences. After all, Jesus was sent to unite mankind with God so that we may have a relationship of love and grace with Him and earn a place in Heaven.

The canvas measures 290 by 165 cm and it would have originally hung above an altar. Light comes in from the right-hand side, illuminating one side of Jesus’ body and highlighting his white loincloth or perizoma, starkly contrasting to the enveloping darkness. Flickering candlelight would have emphasised the strong chiaroscuro and enhanced the muscular quality of Christ’s deathly-pale body. The illusion that the cross is pushing out of the canvas surface also helps to reduce the space between viewer and subject, cropping the field of vision to concentrate the eye on the subject at hand. Zurbarán had initially trained as a sculptor, and consequentially the bodies in his works have a weighty, earth-bound quality. I think this is also the source of his understanding of dimensionality and perception in composing a painting like this. I imagine that if this artwork were seen in a dark space at a distance, the shadowy background would blend in with its surroundings and could be mistaken for an apparition or a sculpture. The cross could appear to be floating, the body of Jesus almost weightless as if he is standing rather than being nailed in position. It is interesting that his feet have been pinned individually, something that is often seen in Spanish images of the crucifixion. Positioned below his feet the onlooker would have a view of Jesus’ face, putting us in the place of those who were present at the crucifixion according to the Bible. Astounding illusionism paired with convincing realism brings us close to touching distance of the divine body of the Son of God. With characteristic virtuosity and inventiveness, Zurbarán takes this notion further with a scrap of paper at Christ’s feet upon which the date of the painting is written. A controlled palette and the subtly rendered textures (wood, nails, skin, cloth, paper) do not divert our attention, but rather add to the tangibility of the ‘vision’.

Compared to both earlier and later paintings of the same scene there is less drama and less noise in Zurbarán’s Crucifixion. The silence works to its advantage as we are left undisturbed to focus on our own thoughts. This is the core purpose of the artwork; to be a vehicle to private devotion and introspective contemplation. Images are in many ways more powerful than words as they can exist in our physical space as well as being committable to memory. I think this may be the one that I see in my mind’s eye when I think of all the crucifixions throughout art history. The Dominican monks who looked upon this painting would have known what the Bible’s said about the death of Jesus, so would not have required a didactic image that would have suited a church for laypeople. This painting had a function to fulfil as a visual aid to emphatic and experiential piety. It allows the viewer to meditate on the concept that Christ suffered and died for mankind. He was the sacrificial lamb, which consequentially is the subject of a later work by Zurbarán, Agnus Dei (c.1635-40), a painting that possesses an intense spirituality which is so characteristic of the artist.

Without agonised, grief-ridden faces, spurting blood or a gruesomely realistic corpse, the power of this painting is found in the potential of the onlooker’s religiosity. Despite being created for a monastery Zurbarán’s Crucifixion is far from being sober or dull. He returned to the subject around 12 times through his career, but I think this version is his greatest. He employs his technical ability to create a vision that is moving, instructive and beautiful. It stirs the soul, speaks of mortality and suffering, providing a visually vivid and profoundly enduring reminder that whatever we suffer in our lives it is nothing in comparison to Christ’s suffering for humanity. It is an image that should both challenge and settle our inner conflicts, providing comfort and strengthening our forbearance. The death of Jesus reverberates in the darkness of this painting, but it is a death with hope.

St Teresa of Ávila’s motto seems a good way to conclude – Lord, either let me suffer or let me die