Leonardo: Experience a Masterpiece

National Gallery, London

Until 26th January 2020

When it comes to art exhibitions, I consider myself something of a traditionalist. Words such as ‘digital’, ‘immersive’ and ‘interactive’ used in conjunction with ‘exhibition’ usually make me wince. However, in the Curator’s Talk for Leonardo: Experience a Masterpiece at The National Gallery (https://youtu.be/7Yh5Lu6a1YU), Dr Caroline Campbell discusses a shocking statistic; that the average time a gallery visitor spends in front of an artwork is fifteen seconds. Not only does this present an enormous challenge for the organisers of exhibitions, but it raises issues about how we as visitors experience art today. This exhibition seeks to provide a remedy to these very modern problems by harnessing technology to tell the story of the gallery’s most famous Leonardo work, The Virgin of the Rocks (about 1491/2-9 and 1506-8). As a frequent gallery visitor who spends much more than a few seconds in front of an exhibit, I was interested to see The National Gallery’s response, so I put aside my scepticism and went to the exhibition with an open mind.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin of the Rocks, about 1491/2-9 and 1506-8, oil on panel, 189.5 x 120 cm, National Gallery, London

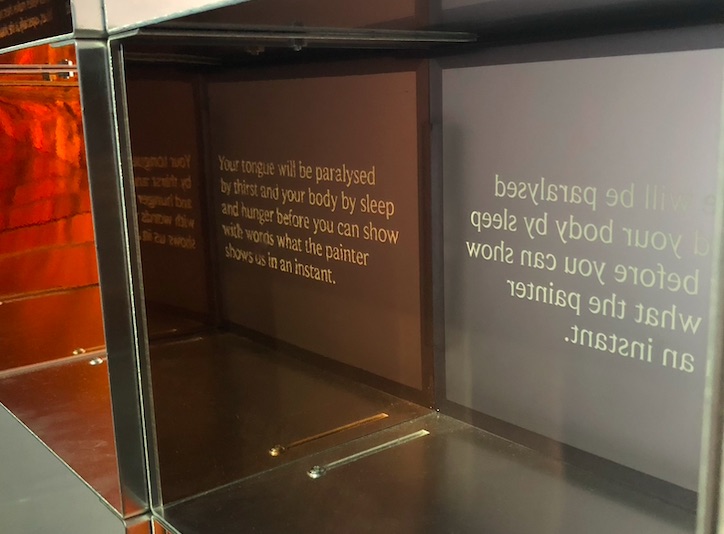

The Virgin of the Rocks is usually on display in the Sainsbury Wing of the gallery, almost always surrounded by a crowd of noisy spectators. Interestingly, and to great effect, the painting is located in the final room of this exhibition, leading the path of the visitor through three designated rooms, The Mind of Leonardo, The Studio, The Light and Shadow Experiment to The Imagined Chapel, where the masterpiece is unveiled. Luring the visitor with a trail to follow opens up a dialogue about the creation of the artwork before permitting a view with (hopefully) fresh and informed eyes. In the first room, The Mind of Leonardo, we encounter two walls of metal boxes. From a distance they reveal landscapes of the Dolomites in Northern Italy which are considered to be the inspiration for the setting of Leonardo’s great painting. The sound of trickling water evokes area of natural beauty and its rivers. Moving around the room creates transitions which offer new views, and upon close inspection some of the boxes contain writing in English, Italian and Leonardo’s famous mirror writing. This spontaneous and free-flowing interaction both from a distance and close encounter sets the pattern for the following rooms.

‘Your tongue will be paralysed by thirst and your body by sleep and hunger before you can show with words what the painter shows us in an instant.’

In The Studio we enter a staged scene transformed by light from the workshop of an artist to that of a painting conservator. An animated slideshow is projected onto a blank screen set up on an easel, explaining the underdrawing, layers of paint, pentimenti and even a clever juxtaposition of the Gallery’s version of the subject with that in the Louvre (1483–1486). I found this to be a very interesting way of deconstructing the painting and demonstrating Leonardo’s working methods. It also gave an insight into the world of the expert conservators in the conservation department, more information on which was found on mock-desks set up around the room displaying object files and notes. Spending several minutes watching the projected canvas, the visitors could then explore the room in their own time, examining documents and equipment hands-on – a very different experience than the typical labels and panels exhibitions usually offer.

The following room, The Light and Shadow Experiment, displays three boxes encased within a wall, containing a plaster head, a roughly hewn lump of rock and a collection of three-dimensional shapes respectively. Unlabelled levers on the outside invite visitor participation, the sliding of reveals their purpose as light dimmers. Spending a few minutes playing was surprisingly satisfying, allowing us to see how lights play upon a surface and create different shadows, textures effects and moods. Around the corner a more elaborate experiment awaits. A large screen showed an artist’s model posed as Leonardo’s Madonna. A touchscreen dial allows the user to move the light source 360° around the scene, elaborating on the simpler light experiments just witnessed. Of course, Leonardo would have calculated the effects of light and shade without this advanced technology, but nonetheless the results of the creative and considered activities on someone unfamiliar with the inner workings of an artist’s mind prove to be thought-provoking and fun.

The Imagined Chapel, the final room, containing The Virgin of the Rocks proves to be the most powerful. The Leonardo painting is hung on a blank wall which, by the power of projection, comes to life to show a series of speculations on how the whole altarpiece may have looked. The surviving contract of 1483 tells us that Leonardo and Milanese half-brothers Ambrogio and Evangelista de Predis were hired to paint and an altarpiece by the Milanese sculptor Giacomo del Maiano. The document scrupulously outlines what the patron, the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception at San Francesco Grande in Milan, wanted from the artists. As the subject matter of the scheme was to relate the Immaculate Conception (a topic only recently sanctioned by decree at this time) and so Leonardo had some freedom to create a new kind of religious image. He chose to paint the Virgin seated on the ground in a rocky landscape. Prior to this, the Mother of Christ was usually depicted enthroned majestically, historically against a golden to signify heaven. The background, as the first room revealed, was inspired by the Dolomite landscapes Leonardo had so carefully studied. Here, Leonardo uses the natural world to create a stage for this Madonna of Humility. The metaphors within the naturalistic details of rocks, flowers and water would have been significant to the Franciscans, whose founder Saint Francis renounced his worldly goods to pursue a life of poverty and who is strongly associated with the natural world. The signature sfumato and contrapposto of the artist reveal the grace of Mary, Christ, John the Baptist and the angel, and set them apart from us in an almost otherworldly way. This quality contrasts with the fidelity with which Leonardo has observed the naturalistic setting. The beauty of the figures denotes their divinity, whereas the traditional haloes and wings of the angel are almost imperceptible in their subtlety.

The atmosphere in this last room was quite surprising. The lighting makes The Virgin of the Rocks shine in a way I’ve never seen it before, with the blues glowing like stained glass and the golds almost reflective. The painting is usually displayed in the same room as the Leonardo cartoon at the gallery, and so is usually lit very low in order to help preserve the paper. The choral music created a sense of what it would be like to see this painting in a church, and a fake altar table in front of it seemed to encourage visitors to stand before the painting and projected altarpiece and look up in reverent silence. Witnessing this was a remarkable thing, and demonstrated how altarpieces could be exhibited in such a way as to fully appreciate their original function as objects of devotion. When it comes to displaying and curating, altarpieces present their own particular issues. Being typically custom made for a specific place (both geographically and within a church) they are a result of their patron and purpose. The latter is often in conflict with the aims of the average gallery viewer. An altarpiece is intended to preside over a sacred space and be used as an aid to religious contemplation, whereas the typical visitor to an art gallery seeks to view the displays as objects to be admired for their aesthetic qualities and all too often to be ticked off the list of things to see. These days it is common in major tourist attractions like The National Gallery, that the phenomenon of the camera phone has resulted in visitors attending with a panicked agenda – to get a photo of all the masterpieces. All too often I see people looking at a painting through their camera, not with their eyes, snapping a perfectly aligned image for their Instagram account before moving onto the next one. Perhaps seeking to turn the tables on this misguided modern experience of art, the very focussed nature of this exhibition may help to correct the fast-paced, image collecting issues of the age. Considering Leonardo’s passion for the latest technological advances of his day, and indeed a designer of radical inventions of engineering, one may see how he would have appreciated this attempt to enhance what is already an undisputed masterpiece.