Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up

Until 4th November

Victoria & Albert Museum

Like many others, I have a soft spot for Frida Kahlo. I admired her work as a teenager and became fascinated with her brutally honest, dream-like paintings. As a result of her deeply personal work and the physical and mental turmoil she lived through, we get a feeling of familiarity from Kahlo. And yet she has an enigmatic mien. A celebrity of the art world and a cultural symbol, her face is one of the relatively few of artists through history that is instantly recognisable. That famous ‘monobrow’ is synonymous with her name, like Dalí’s twizzled moustache or Warhol’s wacky white wig. By displaying her paintings, clothes, medication and make-up this exhibition seeks to reveal the woman behind that iconic facade.

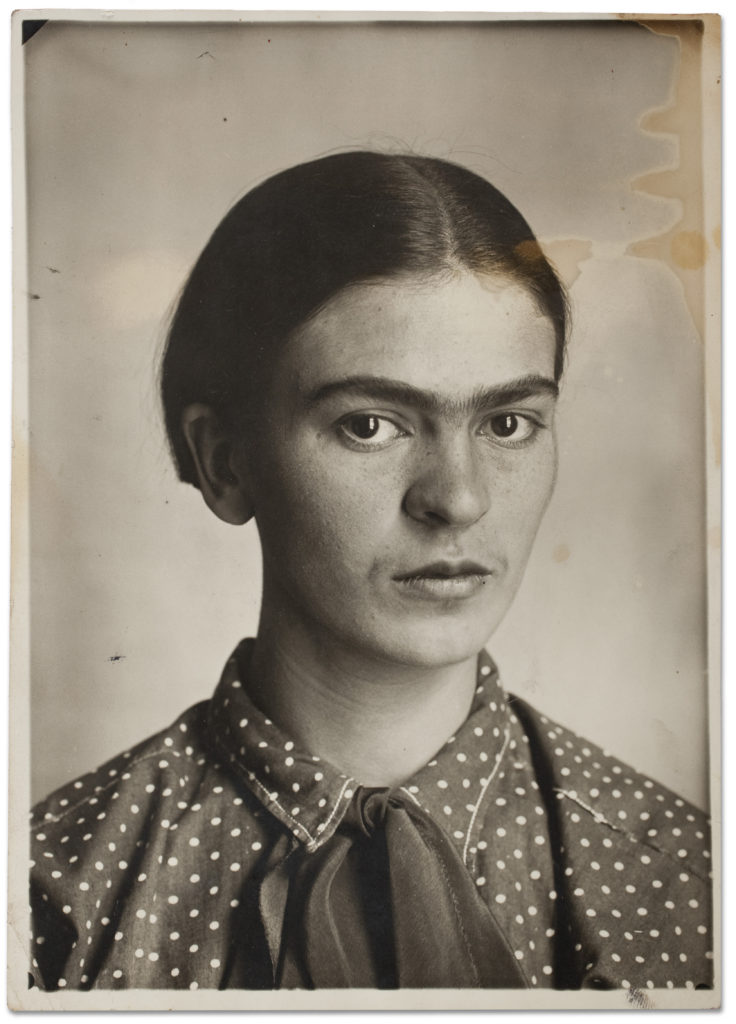

The opening rooms are filled with photos of Kahlo’s family and her childhood. It is clear that she grew up with a strong sense of individualism, a curiosity about her identity and a yearning to grow and explore the world. We know that her youth was riddled with illness. At six years old she contracted polio, which stunted and withered her right leg. At 18 she was in an accident involving a bus, which left her with injuries that would endure through her life. These incidents would be a curse and a blessing, leaving her bed-bound for long periods where she could concentrate on her art, her creativity constantly inspired by the pain that put her there. The photo below was taken by her father when she was around 19 years old. Guillermo (or Carl Wilhelm, to use his German name) was an accomplished photographer, documenting the modernising architecture of Mexico City in the late 19th century. He was well-read and creative, and encouraged Frida’s artistic pursuits after her accident ruined her plans of studying medicine. Frida is wearing in a jazzy shirt and necktie here, with her hair is scraped back in a harsh, masculine way. Her large eyes are wide and her gaze is boldly interrogative but not unfriendly. In early photos such as this, we get the feeling that like most young people she is searching for herself and establishing her style. Another photo on display here shows her in her father’s three-piece suit, ill-fitting but making a statement. Frida said that her father was a ‘magnificent person’, and within the photos he took of her we see how the lessons learnt from sitting for Guillermo’s camera continue through to her self-portraits in front of a mirror.

Frida Kahlo, c. 1926. Museo Frida Kahlo. © Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Museums.

In 1928 Frida joined the Mexican Communist Party, through which she met fellow-painter and her future-husband Diego Rivera. She referred to this meeting as one of ‘two great accidents in my life’, the other being hit by a bus, and tellingly added that ‘Diego was by far the worse’ of the two. They married the following year, and regardless of an age difference of over 20 years, the fate of ‘the elephant and the dove’ would be forever intertwined. Rivera had gained important commissions to paint large, often politically-fuelled murals, while Frida’s work remained relatively small in scale and was always introspective. Although Rivera was by far the more renown, and despite the difference in their output they had a mutual respect for one another’s work. Rivera said that Frida’s painting had ‘an unusual energy of expression, precise delineation of character, and true severity… It was obvious to me that this girl was an authentic artist’. Frida had received no formal artistic training, but her long periods of recuperation in bed, fitted-out with an easel and mirror, nurtured her natural talent and gave her fuel for the imagination. The horrific bus accident had broken Kahlo’s body. An iron handrail impaled her through the pelvis, and she suffered a fractured collarbone, ribs, pelvis and legs, and three displaced vertebrae. The injuries took months to heal, but the residual pain would last for the rest of her life.

Among the exhibits here are many of Frida’s own clothes, the traditional style of which was influenced by mother’s Spanish-Mexican heritage. Colourful and voluminous, the garments she chose to wear concealed her body (in particular her so-called ‘ugly’ leg) and gave her another outlet for her artistic expression. Some of her makeup is also on display, notably her famous red lipstick and nail polish, but I think the most personal objects are her prosthetic leg (see image below), spinal braces, and orthopaedic corsets. They became a part of her, fitting and moulding to her body, supporting her and helping her to heal. She decorated them with paint, mirrors and bells. Displayed on mannequins they give a more powerful sense of Frida’s presence than the facade of clothes and makeup. One corset in particular has a hole cut out where her abdomen would have been, telling us of the difficult and painful time she experienced when she miscarried in 1932 and led to her being very ill as a result. These objects are paired with her writings of what could have been a ‘Dieguito’, and illustrations from anatomical diagrams.

Prosthetic leg with leather boot. Appliquéd silk with embroidered Chinese motifs. Photograph Javier Hinojosa. Museo Frida Kahlo. © Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Riviera and Frida Kahlo Museums.

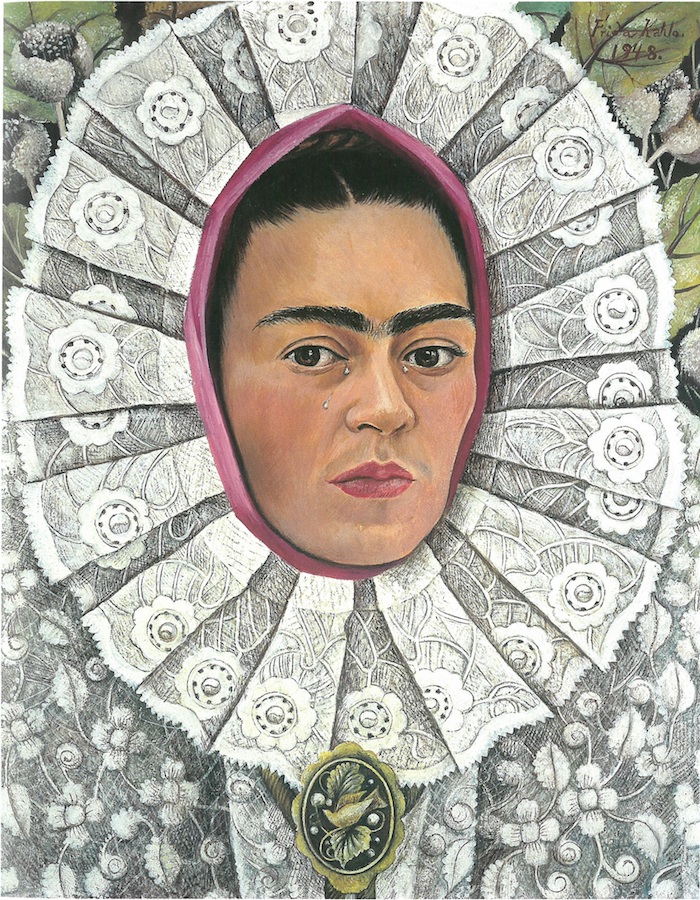

I was excited to see some of Kahlo’s self-portraits in the flesh, and this one below, painted 1948, stood out. Compositionally it is very interesting. Her head pokes through a quite flat, densely patterned backdrop. The traditional ceremonial Mexican headdress forms a mandorla around her face, like a halo of starched white lace, a device usual in the depictions of Christ or the Virgin Mary. This holiness is taken further by the tears that fall from her eyes, mimicking the weeping statues and paintings of the Mary. She is a strangely otherworldly vision of chastity and purity. Many photographs of Kahlo exist, and in almost all of them her large brown eyes stare out at the viewer, ambiguous but compelling. But unlike the photos, her self-portraits were done before a mirror, so there is a sense that the gaze is directed at herself, searching and questioning. ‘Of my face I like the eyebrows and the eyes’, she said, ‘Aside from that, I like nothing.’ I find heer severe honesty and constant modesty attractive qualities. It would perhaps be considered strange that she painted herself so much, were it not for the fact that it is the inner-self that is being revealed.

Frida Kahlo died in 1954 at the age of 47. Rivera locked her belongings away at La Casa Azul, their shared home in Mexico City, stating that it could not be opened until after his death. Many of the objects on display here at the V&A are from that room, providing us with an extraordinary portrait of an artist so many feel an affinity with. She famously said ‘I paint my own reality’, but her reality has become one which many people share, no matter different their lives in comparison. It is her ability to connect with people through her individuality, suffering and self-transcendence that makes her so loveable.