Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art

National Gallery, until 22nd May 2016

King of the French Romantics, Delacroix has long been a favourite of mine. In this groundbreaking exhibition the enduring legacy of a revolutionary painter is explored, hanging his works beside those of his descendents. He had said that paint was ‘only the pretext, only the bridge between the mind of the painter and that of the spectator’, suggesting a higher, perhaps more spiritual form of communication. He broke the rules, did things nobody else was doing at the time, while showing an understanding of art history and demonstrating his skill as a painter.

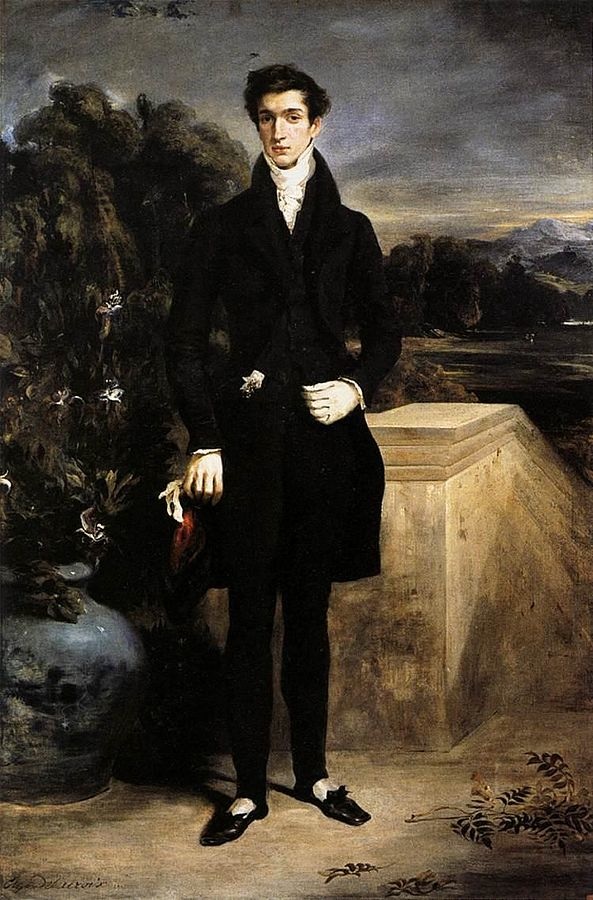

A work that I was excited to see was the portrait of Louis-Auguste Schwiter or Baron Schwiter, a print out of which had adorned my bedroom wall at university, my fantasy art collection. Delacroix painted this after a trip England, where he visited the prominent portrait painter Thomas Lawrence. His influence is obvious in the compositional format of the painting; the full-length, poised stance, the use of architectural detail, the aura of personality; but there is something which remains purely Delacroix about it. The landscape and his clothes are dark and brooding, the inclusion of lilies tie together the white details of his skin and cravat, he holds his hat and one glove in his hand, giving us a sense of either his coming or going. The man is a well-dressed, handsome, romantic-type, well-bred and intelligent, and all of this is given by a tilt of the head and the slight raising of an eyebrow. The work was rejected by the 1827 French Salon in which it was exhibited, and Delacroix subsequently reworked parts of it, maybe to make it more acceptable. Degas later brought it, where he proudly displayed it in his studio for visitors to see. If nothing else it shows how Delacroix did not totally dismiss tradition and was aware of fashions of the time. He could turn his hand to works like this, and execute them uniquely.

One young painter that saw this work was John Singer Sargent, and across the gallery is his portrait of Lord Ribblesdale (1890), which clearly shows Delacroix’s influence. The same pared down detail and almost confrontational attitude of the sitter is evident in this portrait, and this format becomes Sargent’s default. There is a transitory feel to the pose, as the above, like the sitter is on his way out the door. The subject isn’t sitting for the portrait in the traditional sense. Parallels can also be drawn from the brushwork, and both painters apply it with expression, focusing on details to draw our eye to the faces. Lighting half of the face exaggerates the features, bringing a degree of depth that the rest of the painting does not have. The both backgrounds are rather vague, giving emphasis to the subject while creating an atmosphere for the subject.

A more characteristic side of Delacroix is visible in The Barque of Dante (1822), which is packed full of drama and energy. In a way, knowing what the subject here is does not matter. And as with other literary or allegorical theme that Delacroix depicts, you can read the painting through feeling it. The vivid tones are used to pick out key characters, emphasising their theatrical poses. The mass of writhing bodies in the water and clinging onto the boat are reminiscent of Rubens in their fleshiness. The tumultuous sky looms over the scene and draws the eye to the horizon. I get a feeling of mixed temperatures, in cool water and the hot clouds, and sound from the struggling bodies. In this way it is a very sensual painting.

And I think the same can be said of Van Gogh’s Pietà (after Delacroix) (1889). The body of Christ has that dynamism that can be seen in the work above, and there is a similar rough, sculptural feel. I don’t think that I would ever link Delacroix to Van Gogh, stylistically or otherwise, but I appreciate a new context here. The expressive use of colour is probably something that Van Gogh directly took from his predecessor, who was the master of applying tone in order to get an emotion across. Delacroix increasingly removed any traditional sense of narrative from his works, and this influenced the younger generation of painters working in Paris. With Van Gogh’s Pietà here, the narrative and degree of realism is not important, it is the transmission of emotion through the paint that is paramount.

Pietà (after Delacroix) (1889) by Vincent Van Gogh, oil on canvas, Vincent Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

The last Delacroix painting that I want to talk about was one that I spent a long time looking at, which is this, Ruggiero Rescues Angelica (c. 1856). Inspired by a poem (Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso) it carries the lyrical qualities of words through paint. Telling of the progress towards the modern, Ingres painted the same subject matter over a decade before and the contrast is clear (https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/jean-auguste-dominique-ingres-angelica-saved-by-ruggiero). In this interpretation Ruggiero is the focus, and Angelica is pushed into the background. This strengthens the action, the movement, the noise of the scene. Eliminated is the feeling of myth (Ingres has Ruggiero riding a hippogriff – half horse half griffin), and even the monster is more believable here. It is very sketchy, up close you can see the texture of brushstrokes. The colours bring the picture to life. Despite the lack of anatomical correctness and perspective I find the work fascinating. This would have been seen as unfinished in the mid 1800s, but Delacroix might have said that it was open to interpretation.

Gustave Moreau’s Saint George and the Dragon (1899-90) borrows from Delacroix painting. The jewel tones and compositonal mastery create an impact, showing that realism is not the only way to evoke emotion. The landscape here has been used purely as a backdrop, something that is supposed to act as a stage for the unfolding scene. The glimmering armour, the billowing cloth and the movement in the rearing horse build up to the apex of the drama, the striking down of the beast, which although we do not get to see in the painting, we can continue in our minds.

Saint George and the Dragon (1889-90) by Gustave Moreau, oil on canvas, © The National Gallery, London

The groups of works around those of Delacroix’s on display here at the National Gallery demonstrate a direct inspiration and reverence for what he did for modern art. Van Gogh said of him that he ‘speaks a symbolic language through colour itself’, something that he would later become known for. The idea of tones being visual substitutes for words and emotions was not a new thing; think of readable religious paintings with their colours loaded with meaning – white for innocence, red for the Passion etc. But Delacroix was responsible for applying the purpose to a personal expression, a device to draw the eye around a canvas and have our feelings directed by what he wants us see, then leaving us to continue on our own. The relationship between different shades was experimented with too, contrasting tones to create feeling, in an almost scientific way. Colour theory would later become a serious study of this. In hindsight we can see just how important his ideas were, but he provoked both admiration and criticism in his lifetime. Delacroix’s avant-garde spirit was revolutionary; he was a progressive, sensational and passionate painter. Baudelaire famously said of his friend Delacroix that he ‘was passionately in love with passion, and coldly determined to seek the means of expressing it in the most visible way’.