Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art

The British Museum, 26 March – 5 July 2015

Beauty is something that is easily identifiable and usually unquestionable. Marilyn Monroe: beautiful. Sunsets: beautiful. Kittens: beautiful. A beautiful thing has the power to make us gaze in wonder, admire nature and contemplate life. But how has the concept of what we consider to be beautiful changed over the past 2,500 years? The encapsulation of beauty in the human form is something that the Ancient Greeks defined, not purely as a visual thing but as an embodiment of theological, philosophical and ideological values. The examples on display here at the British Museum are beautiful objects, but they also give us a wonderful insight into a civilisation that is actually not so very far away from our own.

The Oxford dictionary defines beauty as ‘a combination of qualities, such as shape, colour, or form, that pleases the aesthetic senses, especially the sight’. Ancient Greek sculpture fits this definition, although I often forget that everything would originally have been painted in resplendent colour. We think gracefully posed, perfectly proportioned bodies, with symmetrical and delicate facial features, naturalistic but idealised, exemplary specimens of the human race. The sculptors themselves were masters of their art. The first sculpture I encountered was this, A River God (probably Ilissos), from the West pediment of the Parthenon (c. 447–433 BC). Despite being damaged and missing its head and extremities, it is a powerful and imposing vision To the Ancient Greeks the gods were the ruling force, a rank of deities immortalised in myth. The people built colossal temples to appease them, embellishing them with sculptures such as this. The muscular body reclines on its left side, the torso twisting towards us, his brazen nudity exuding all that defines male dominance. The flowing drapery over his left arm is indicative of the deity’s custodial charge on earth; water. The sculptor has imprinted the values of beauty onto the male form; muscle, youth and perfectly measured proportion. A male body worthy of a god, the strength of his command translated into flesh.

River god (possibly Ilissos) – from the West pediment of the Parthenon (c. 447–433 BC), British Museum, London

As with the River God above the Parthenon Iris (ca. 447–433 BC) is a translation of the divine through the human form. The goddess Iris is messenger of the gods, usually depicted with wings so that she can travel from the realm of the gods to earth as a herald. Here we notice that the body is clothed, swathed in a thin material that moves as though she is coming into land. Her dress does little to conceal the figure beneath, voluptuous and fertile Isis has the ideal female body. Contrasting with the male figure above we could glean that beauty is inextricably linked to an innate human attraction and physical requirement in both sexes. The male as a symbol of strength, a defender and protector, a tangiable manifestation of his ability whereas the purpose of the female form is maternal, sensual and ripe, with strength of a different kind.

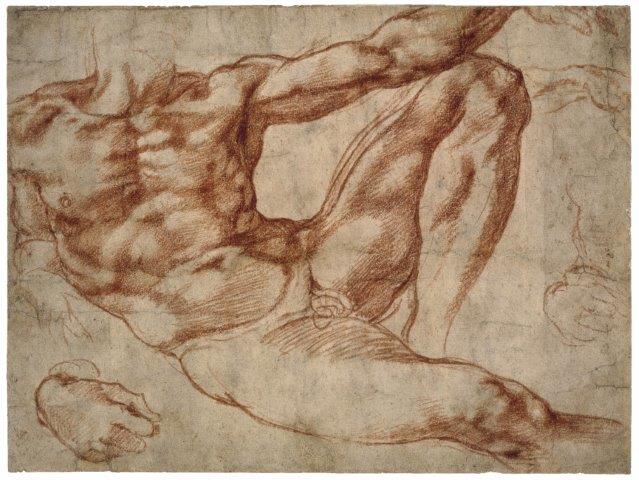

After rooms of objects I knew nothing about Michelangelo‘s Study for Adam (c. 1510-11) was a reassuring sight. The Renaissance sought to revive the art of Antiquity, and I think Michelangelo did this in the most direct way, especially in his sculpture. He infused his works with an understanding of Antiquity, both its art and philosophy, with a Humanistic view. This preparatory sketch for the Sistine Chapel demonstrates the influence of Ancient sculpture, here applied to his depiction of the first man created by God, Adam. This small but impressive drawing is juxtaposed with the Belvedere Torso from the Vatican collection and a reclining male nude (again from the Parthenon) which give a strong visual comparison and show Michelangelo’s admiration and respect for the past.

I think what even the most ignorant of people (I am referring to myself here) can assimilate from this exhibition is that beauty has not changed very much. Of course there have been fashions – thinking specifially of women through history, in the Renaissance where plumpness equalled wealth (Rubenesque), the 1920s fashion of willowy bodies and curve concealing flapper dresses, to the perfect hourglass of Monroe in the 50s. The Greeks trusted in mathematics to provide measurements and proportions, but the perfect body isn’t just about numbers, it is interconnected with our ideals as a species. Art of Ancient Egypt was static and wooden, but the Greeks projected realism onto their sculpture, creating flesh and fabric out of stone. Sculptor Polyclitus achieved this through symmetria (aesthetic theory of balance and counterbalance) to create dynamism, the contrapposto being highly favoured. Emotion and motion in the sculptures on display here show an accurate observation life, which makes them accessible and understandable. The science of what we as humans find appealing (boiling it down to male virility and female fertility) is something that cannot be purely visual. It is a sensual thing, and the layout of this exhibition by themes of human feeling underlines this.