Botticelli Reimagined

5th March – 3rd July 2016

V&A Museum, London

We all know Botticelli. We know his deptictions of beautiful Venuses and Virgin Marys, or portraits of rich young men in their finery. His is a name that evokes a mysterious and magical style, always with an undertone of the spiritual, mythological or intellectual. He fused tradition and innovation, and created for us a glimpse into the Florentine Enlightenment. But what of Botticelli’s legacy 600 years later? Is he still relevant today? Can his ideas adapt to our culture? The V&A’s vast blockbuster shows us, on a journey from the present day back to the quattrocento.

The exhibition opens with the present day, showing how Botticelli is constantly rediscovered and reinterpreted. From Lady Gaga’s ‘Artpop’ album cover to OZ alloy wheels designed (according to their website) ‘in search of a timeless absolute beauty’. The Renaissance master inspired designers and artists of all art forms, including fashion and photography. Paul Himmel’s Botticelli Girl (1950) – sorry, I could not get a reproduction, but do look it up – shows a beautiful youth, the qualities of innocence and ethereality reborn in a 20th century muse. Not surprising, as Boticelli’s work has been translated by photographers many times, notably by David LaChapelle. And Neoclassical painters borrowed from Botticelli, sharing his love of Antique sculpture and style. An example by Antonio Donghi called Donna al Caffè (1931) is of a Botticellean blonde transported into the 20th century.

Dante Gabrielle Rossetti was obsessed with Botticelli, and his melancholy female subjects were heavily influenced by him. Rossetti and the other Pre-Raphaelites admired the intellectual element of Botticelli’s work, and themes from mythology, Classical and Renaissance literature dominated the movement. Of course the education of any artist required the study of the Italian masters, copying to understand the principles of art. Rossetti must have found an affinity with the works of Botticelli. Most visibly he must have found inspiration in his portraits of women, and he soon established, as Botticelli did, a specific type. But whereas Botticelli’s are usually tall, lithe-bodied blonde beauties, Rossetti preferred a more shapely, pale redhead, with large eyes, a long nose and voluptuous lips. This iconic female can be seen in La Ghirlandata (1873), which displays some adoption of Botticelli’s style in it’s simplified composition and a flatness that is evocative of a past age. Other Pre-Raphaelites and artists it’s orbit are represented here, such as William Morris‘ beautiful Orchard Tapestry (c.1890), Eleanor Fortescue-Bricksdale‘s Botticelli’s Studio, Evelyn de Morgan‘s Cadamus and Harmonia (1877).

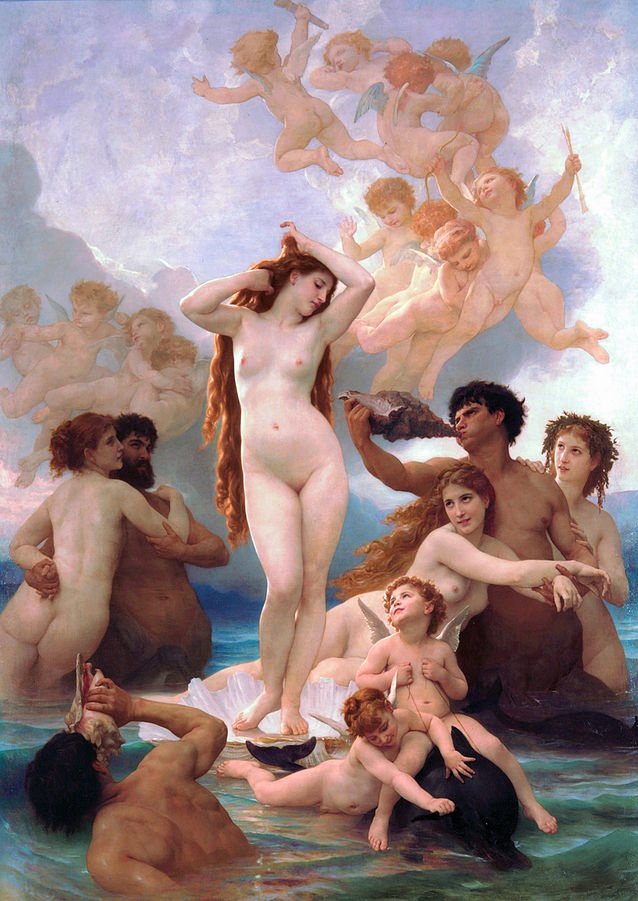

More classicist artists such as John Flaxman and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres were also inspired by Botticelli, in particular the grand mythological allegory as seen in The Birth of Venus. William Adolphe Bourguereau interpreted the painting in his uniquely lyrical way, candy coloured and ethereal. His Venus is more shapely, more realistic, more modern. Her auburn hair cascades down her body. In that elegant contrapposto the goddess looks away from us, rearranging her hair, and is oblivious to the attention from her otherworldly admirers. Standing in her shell she is surrounded by cherubs and centaurs creating a carcophony with conch shells. But she is silent, statuesque and oozing elegancy and purity.

Vasari said of the artist that ‘Sandro, who was a ready fellow, had devoted himself wholly to design, became enamoured of painting and determined to to devote himself to that’. Disegno, the focus on defined outlines, strong colour and flat surfaces, was to become Botticelli’s lasting legacy to Florence, his hometown. It became a quintessentially Florentine thing, later made famous by Michelangelo. With the identifiable palette of golden tones, hues of cool blues, rich greens and pale pinks, Botticelli was imitated but no one could rival him. During his career he was well patroned, most notably by the Medici, the powerful family who nurtured a cultural enlightenment. Florence became an artistic and economic power, and as a result there was an increase in artists guilds and workshops. Botticelli’s employees worked so closely with their master that correct and undisputed attribution can be problematic. Portrait of a Lady known as Smeralda Bandinelli (c.1470-5) was a work that divided opinion until its authenticity was verified in the 1930s. The portrait is full of life and realism. This is a defined move away from stiff and stony Medieval portraiture, and a quintessential product of the Renaissance. We get a sense of the sitter’s personality, her face has expression and she stands naturally, as though not really sitting for the painting but caught unexpectedly. Although there is an inclusion of classicism in the traditional sense, she is thoroughly modern, of her time.

Portrait of a Lady known as Smeralda Bandinelli (c.1470-5) by Sandro Botticelli, tempera on panel, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

I have focused on paintings that revolve around female subject matter, an intentional move to focus on specific works in this vast exhibition. Grace and elegance are synonymous with Botticelli, and thereafter the Italian Renaissance, specifically in Florence. His ideas defined the ideal female form, one that has endured through the centuries to today and spread from West to East. But Botticelli and his workshop produced hundreds of works, covering the genres of portraiture, mythology and religion. With the later religious paintings there are signs of the effect of that religious fanatic Fra Savonarola. But Botticelli did not give up his Venus. Here in Virgin and Child with the Young St John the Baptist (1480s) we see Botticelli’s lifelong muse, the blonde-haired beauty widely regarded to be Simonetta Vespucci. Here, rather than a goddess of myth she is the mother of Jesus. Just as the Christians converted pagan gods and goddesses to figures from their own religion, so does Botticelli. And why not, she was, and still remains a symbol of perfection and pure beauty. A symbol of love.

Virgin and Child with the Young St John the Baptist by the workshop of Sandro Botticelli (1480s), tempera on poplar, Städel Museum, Frankfurt

While the Uffizi’s treasures remain in Florence, the V&A have put on a masterful exhibition with so many exquisite works. The time travel from today’s culture back to the 1400s serves to highlight how ingrained Botticelli and specifically his Venuses are ingrained in popular culture and modern day psyche. The last rooms dedicated to Botticelli are magnificent, the starkness of the bright white walls make the paintings sing. The opportunity to see so many masterpieces in one place is sensational. I have learnt so much about Botticelli, how his presence is still felt in Western (and non-Western art today) and how much is owed to him for his enduring inspiration.