Beyond Caravaggio

National Gallery, London

Until 15th January 2017

A day before my birthday this year, Beyond Caravaggio opened. It could have been coincidence, or perhaps the National Gallery planned it especially for me. Either way, I knew what I would be spending my birthday doing. This exhibition is a survey of the enormous influence of Caravaggio (1571-1610) that resonated throughout Europe for years after his death. Unlike many other established painters he did not have a workshop, yet the power of his work spread and was kept alive by his admirers. But why was he so vastly imitated? What was it about his paintings that appealed to artists, and drove them to be inspired by (or just totally rip off) his art?

Antidevuto Grammatica (1571-1626) was a contemporary of Caravaggio, and shared common patrons in the Cardinals Federico Borromeo and Francesco Maria del Monte. The similarities with Caravaggio’s style is at once obvious; the striking naturalism, use of direct light and expanses of deep darkness. Aesthetics aside, there is the focus on a single moment, where something is milliseconds from happening. This is something that our modern eyes take for granted. Composing a painting to capture the pivotal development in a scene hadn’t really been done before Caravaggio. In the Renaissance, fitting a whole story (sometimes even multiple stories) in one image was the norm. This is particularly true of biblical scenes, which the viewer would be able to read, much like a comic book. With ‘everyday’ Roman/urban scenes such as this, we are left wondering what is coming next, and the character’s appearance and pose allow us to guess for ourselves. There is a tension, a claustrophobia in the composition that suggest the ensuing seconds may be violent. The man on the left watches his opponents face intently, leaning across the card table to better read his face. We feel that this card game has taken a turn, and that a brawl may break out depending on the outcome of the second figure’s hand. Grammatica applies light very cleverly, revealing to us just enough to understand the facial expressions, but keeps us interested as we peer in to make out hidden details.

Card Players (c.1615) by Antidevuto Grammatica, oil on canvas, The Wellington Collection, Apsely House, London © Historic England

Guido Reni (1575-1642) is one of the more famous Italian followers of Caravaggio, who clearly learnt lessons from him but infused them into his own style. Reni’s Lot and His Daughters Leaving Sodom (1615-16) has a distinctly classical feel. The figures are graceful, sculptural and composed in a frieze-like manner. We can follow the story through facial expressions and hand gestures, as our eye is led from left to right and back again. The drapery is light and flowing, giving a feeling of movement. Caravaggio’s work has a quality of a moment frozen in time, or a still from a film. Reni’s paintings have a dynamism similar to a dance. Yet this is a strong image, bold and immediate. The women are idealised – in fact their faces are typical of Reni – with beautifully pale and youthful faces, with shapely lips, straight noses and almond-shaped eyes. The proximity of the young lady on the left with that of Lot creates a striking juxtaposition. Young against old, creamy smooth against wrinkled tanned skin. With his blood red cloak, furrowed brow, grey unkempt hair and bushy beard he could have stepped straight out of a Caravaggio painting of Saint Matthew or Peter.

Lot and his Daughters leaving Sodom (1615-16) by Guido Reni, oil on canvas, © National Gallery, London

One of the great Dutch followers of Caravaggio is Matthias Stom, and his Salome Receiving the Head of St John the Baptist (1630-32?) shows the reach of Caravaggio’s influence. The group of bodies (or rather their heads) form an oval, which guides the eye around the characters as we gauge their feelings towards the scene. The backdrop which appears to be a typically Caravaggesque dirty wall does not detract from the narrative, further pushing the action into the foreground. The young boy at the front blocks us out of the scene but provides light by way of a bunch of candles. Salome on the right holds a golden plate aloft to receive the head she so dearly wanted, but her face has a trace of regret as she looks up at it with frightened eyes. Her profile is distinctly classicized, that aquiline flat nose and long neck are from a different time and place to the old woman next to her, depicted with a harsh reality. Caravaggio depicted many decapitation scenes (I can think of 8 individual paintings without looking them up, including two Salome‘s), and he does so with graphic gruesome detail. Stom takes a less gory approach, but the expressions of the figures are just as human in their reaction. The candlelight does differ to Caravaggio’s more emphatic and less carefully observed, but this characteristic became a typical trait of his Dutch disciples.

Salome receives the Head of John the Baptist (1630-2?) by Matthias Stom, oil on canvas, © National Gallery, London

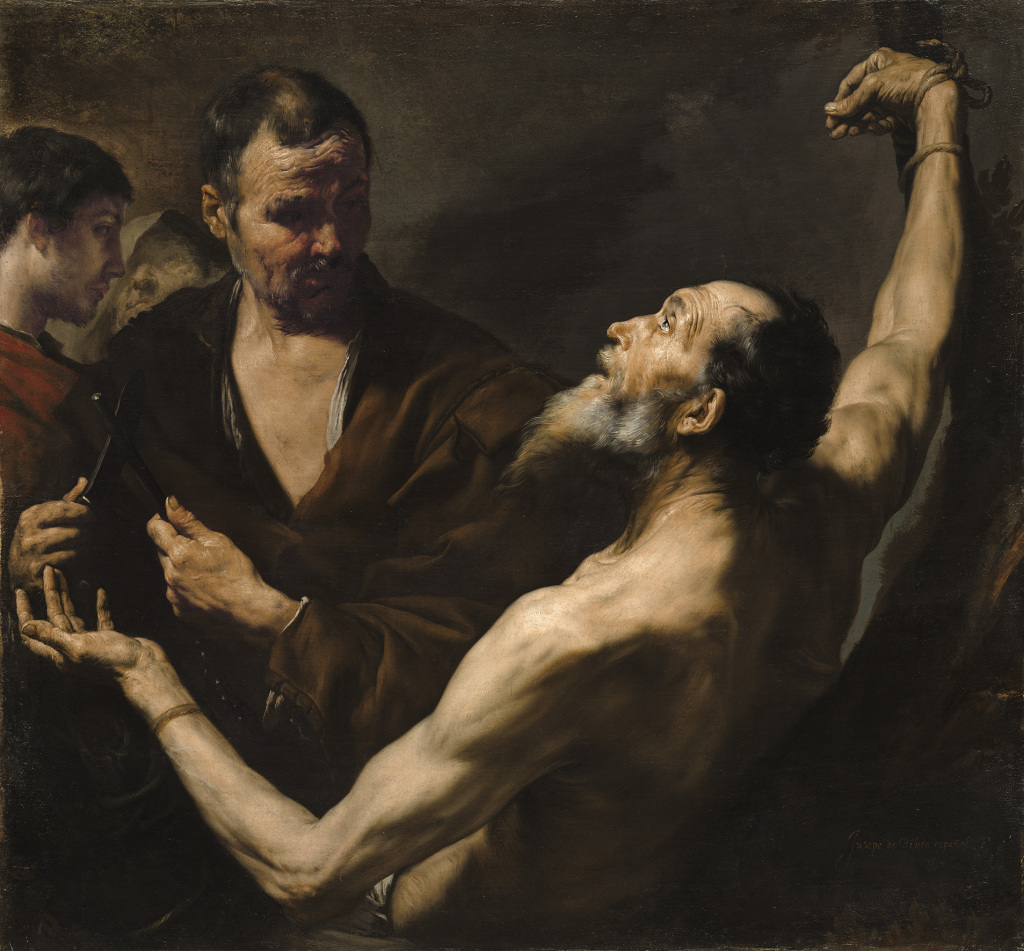

One last work that I must talk about is Jusepe de Ribera‘s Martyrdom of St Bartholomew (1634). There are a few Spanish Caravaggisti who followed their master’s lessons more conscientiously than others, and Ribera is one of them. His extremely pious images harness the full potential of human emotion through expression whilst omitting any unnecessary details. The outcome, as in this work, is stark and often purposefully shocking. St Bartholomew here is clearly of flesh and blood, and we see him as he is about to die, we are thrust before his murderer, who has his skinning-knife in hand. Seeing this painting up close reveal the extraordinary level of detail (specifically in the saint’s ageing skin at his brow and neck, his beard that is painted hair by hair) as well the expressive brushstrokes that make up the background and the two heads at the back left. The earthy palette, strong directional light and close-cropped composition (all borrowed from Caravaggio) and emphasise the humbleness of the apostle as a missionary, his holiness as the light falls on him (no halo required) and the evocation of a desperately real scene from which we – like Bartholomew – cannot escape.

The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (1634) by Jusepe de Ribera, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

It was great to see some of the lesser known painters that followed in Caravaggio’s wake – Lo Spadrino, Carlo Saraceni, and especially Matteo Preti – an exhibition of whose I saw in Syracuse this year, in the church of Santa Lucia with Caravaggio’s masterly altarpiece. I also discovered a couple of artists I didn’t previously know about, Nicolas Régnier and Giovanni Serodine. This show demonstrates the powerful impact Caravaggio had on art history. Not only was he imitated by artists who travelled to Italy to see his works in the flesh, but through the paintings of the Caravaggisti, copies after copies and prints.

But why was he so vastly imitated? Well I think that he was the first ‘modern’ painter in the true sense of the word. He had a knowledge and respect for painters that went before him, but he used that knowledge to create something radically new and completely his own. I think that this inspired the next generation, but more than that he was admired during his lifetime, even by his rivals (namely Baglione). The Catholic Church and the clergy were his main patrons, and could see past his bad temper and inclination for getting into trouble. Because Caravaggio was depicting the ‘real’, it was relatable and sensational and in terms of Biblical stories – didactic to the word.

True, he eventually went too far and fell out of favour, and artistic styles changed so he was largely forgotten. But the idiosyncratic qualities of his painting endured – a pivotal scene from a story that creates tension and engages the viewer, ‘real’ people expressing ‘real’ feelings, an interaction with the viewer based on a comprehension of narrative and emotion, an intelligent application of colour and light to bring it all together – but most importantly to me, and why I love Caravaggio so much, is the psychological dimension to his works which transverses language, culture and time, and that is true sign of powerful art and a painter of true genius.