All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting Life

28th February – 27th August 2018

Tate Britain

Going into this exhibition I wondered what the overriding experience would be from looking back over 100 years of art through a very select number of artists. Expressions of their inner world and responses to the world around them is a theme of constant interest for us as viewers, as we can seek comfort in shared ideas and find commonality as we experience our own self in the world. Seeing a collective response in the form of an exhibition has the potential to be an enriching and exciting thing.

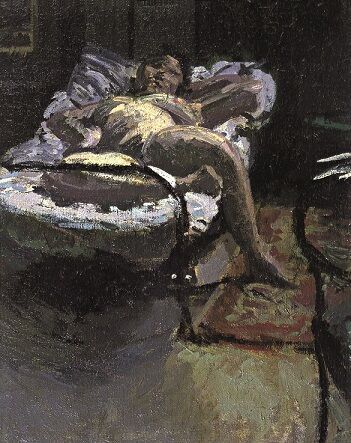

Although the timeline and geography of the artist’s selected for the show are relatively close (there are close links between artists and their tutors, pupils and influences) the selection of works are quite diverse in style. Sickert’s Nuit d’Été in the first room is set among other paintings of the human body, but his stands out and says something specific. Known for his thoroughly modern and shockingly uncensored snippets of London life, this is far from the tradition of painting the nude. It exudes the murky and somewhat uncomfortable and degrading subject of prostitution. Historically the naked female from in art was a thing of beauty, worthy of worship as a symbol of virtue. But Sickert has depicted the raw reality of his society. We see the woman from an unflattering angle, posed awkwardly on the squidgy single bed. Her pale body is heavy and her soft flesh blends into the texture of the bed sheets. Her face is distorted, leaving us to interpret what features we can see for ourselves. There is a hint of a downturned mouth and her eyelids are either lowered or closed to us. I see her as bored, reluctant, tired of her vocation and perhaps life in general. Her lazy sprawl is not enticing or accommodating. The colours of the interior and the woman are drab, dominated by browns and greys. Our role as a viewer is ambiguous and we are left asking what we are supposed to do, or feeling like we want to leave. But I find something compelling in the frank morbidity the scene, and I think Sickert has included a hint empathy to it. The title translates as Summer Night, conjuring up poetic ideas of fading light in idyllic landscapes. Sickert said “The plastic arts are gross arts, dealing joyously with gross material facts” and he sought out his own way to respond to human life that was inextricably tied to his own time.

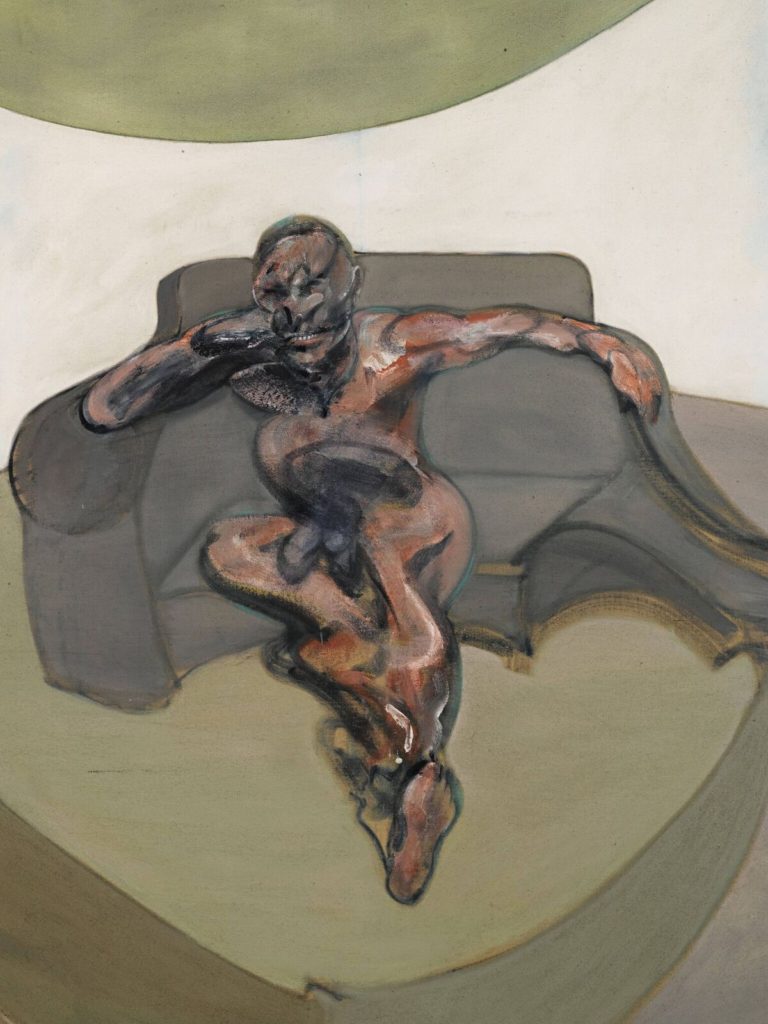

The main attraction to this exhibition for me was the inclusion of Francis Bacon in the lineup. There were many of his paintings in the show, firstly in a room which included Study for Portrait II (after the Life Mask of William Blake) (1955) and a Study after Velázquez (1950) juxtaposed with a Giacometti sculpture. But it was Gallery 8 with photographs by John Deakin, with whom he worked, which interested me the most. Bacon used printed images from newspapers and books as reference points, finding inspiration in reproductions of Old Master paintings and modern photography alike. Portrait (1962) pulls our eye in and gets to the heart of the sitter, a heart that is visceral and reflective of the human condition. What it means to be that person and inhabit their particular skin is something that Bacon is able extract from his sitters, albeit with a little of himself in the mix too. As with Sickert and the nude, Bacon reinterprets the conventions of portraiture for the modern age. It could be seen as unrefined and unresolved. He intentionally abandons any narrative, finding no need to tell us who the sitter is, about their wealth or status, what they do or have done. This is the existential truth, the individual isolated and in undiluted form. Upon further reading the sitter is Peter Lacey, a man with whom Bacon had a tumultuous affair from 1952 to his death in the year of this painting. Knowing this we see to what extent Bacon’s own feelings are entwined in the depiction of the subject.

Portrait (1962) by Francis Bacon, oil on canvas, Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen, © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS, London.

Within a room full of Paula Regos was this painting, The Family (1988), a postcard of which I had stuck on my wall as an art student. There is something darkly fascinating about the narratives Rego explores and the style in which she tells them, always suggestive and open-ended. While some may find this difficult to look at, I love the tension and ambiguity in this tableaux. The figures are weird, some parts of the body are stunted while others look too large. I particularly like the girl by the window, she moves towards the others with an unsettling expression on her face. The picture is full of questions; Are the girl’s hands clasped together in prayer or are they squeezing in anticipation of what is about to happen? What is the relationship between the figures? Is the grey-suited man being restrained or freed by the other two female figures? Looking deeper into the painting, what is the significance of the rose in the foreground? Or the decoration on the dresser at the back of the room, with a stork and a fox at the bottom, and St Joan and St George above? We are left to decide. Perhaps what we choose to see is deeply-rooted within us. The title suggests that this could all come from childhood memories, of which Rego has spoken openly in interviews. She was brought up by dominant female family members when her parents moved to England, her relationship with her mother was not a loving one, she was seduced as a young woman, later abandoned and pregnant. Domestic harmony is not something she experienced. Rego’s paintings often have a sense of sinister psychological, anxious/guilt-ridden characters and an underlying threat of potential violence. Although it would be wrong to think her works completely autobiographical, her identity is entangled in how she expresses herself, and therefore how we see her. How we read the paintings is entirely up to us.

The Family (1988) by Paula Rego, acrylic on canvas backed paper, Marlborough International Fine Art © Paula Rego

Leaving the galleries I felt that I wasn’t entirely sure what I had gleaned from this as an exhibition. Although I am not a fan of many of the artists included (Kitaj and Souza in particular) there are some stunning paintings in the exhibition, and some interesting juxtapositions of works. But I felt that there was too much missing to be a comprehensive survey and a lack of cohesion to bind the exhibits thematically. After the first few rooms I gave up reading the labels and just wandered around. The works by Francis Bacon and Paula Rego were the only redeeming factors for me. Perhaps the curation of the exhibition is trying to get at the fact that life is intangible and elusive. Whatever the conclusion, it was interesting to think about how human experience can be translated into a visual one, and seeing how some artists have attempted to express the physical emotional, and psychological aspects of being through art.