Gothic Tendancies

The Gothic has always appealed to me, even before I knew the word existed. I remember swiping my Mum’s Dracula (1992) video, sneaking it to my best friend’s house and the two of us watching it after everyone had gone to bed. I must have been 9 or 10 years old, I knew that I shouldn’t watch it, and I was scared but nothing was going to stop me. And that was the start of a Gothic obsession; from Goosebumps books to trashy horror movies to forcing myself to go on ghost trains at fun fairs, I loved to experience terror. Since then I’ve read nearly every great Gothic novel written, watched tonnes of films in the hope of being scared, and marveled at the art and architecture which captures the spirit of Gothic.

I have recently been catching up with my TV recordings, including Andrew Graham-Dixon’s The Art of Gothic: Britain’s Midnight Hour which was aired last winter. This three-part series scours the centuries to tell the story of the Gothic from its origins to the present day. In a way only he can Graham-Dixon brings history of the phenomenon to life, explaining how and why it came into being. Born in the Victorian age it was a product of the politics and economy of the time, an era of civil unrest and revolution. Drawing in particular on the labyrinthine qualities of the Gothic, A G-D shows us how it manifested not only in the spooky castles of its novels, but also the cavernous depths of the subconscious. It seems that the Enlightenment was torn between reason and fear, religion and science, a legacy that endures to this day.

On Monday a friend and I had a very Gothic day in London. Firstly we headed to the Royal Academy of Arts to see the Charles Stewart, Black and White Gothic exhibition. I had never heard of Charles Stewart (1914-2001) so this was a real revelation. The one room gallery contains sketches, prints and paraphernalia of Stewart’s, with a focus on his illustrations for J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Uncle Silas (1864), written 100 years after the first Gothic novel The Castle of Otranto by English eccentric Horace Walpole. So as not to spoil the book which I am planning to read I did not do much research. But the story has the vital ingredients of a typical Gothic novel; firstly the heroine Maud, virginal and newly orphaned. The threatening and sinister antagonist Uncle Silas imprisons her in his old house, with dark passages and secret rooms, trying to force her to marry his son so that he inherits her new fortune. I found this useful diagram if you are in doubt that what you are reading is Gothic – http://bit.ly/1no3Sbu which sheds some more light on the story. Even without having read the book you can glean from the illustrations on display here Charles Stewart’s ability to literally translate sentences into scenes. Through the medium of black ink and white highlights the artist creates images of high drama and tension, all in a very stylistically authentic Victorian way.

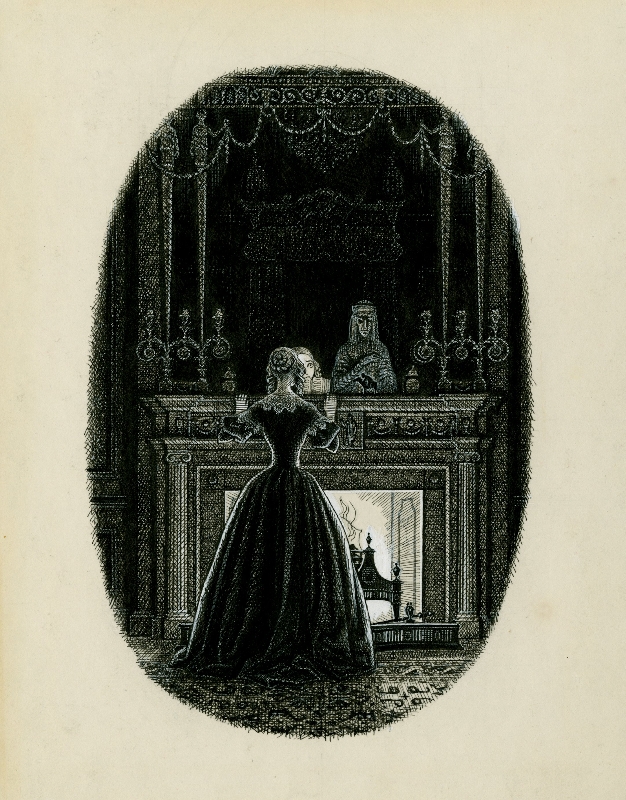

It was interesting that Charles Stewart came across the novel while working as a stretcher bearer during the air raids of London in 1914. The story appealed to his Gothic disposition provided an escape from the war around him. He had been a sickly child, bedridden at times, and spent a lot of time drawing. Stewart later wrote of his family home that “the mysterious upper regions emitted startling creaks and bumps and at times a curious slithering sound”. Like myself he must have had an overactive imagination. After reading Uncle Silas he became obsessed with it, researching every detail of the age even down to the fashion of the time. The emotion of the story is conveyed so clearly that even someone like me who is unfamiliar with the book can feel the dread and terror from the images. I particularly like the illustration below, and the looming figure in the mirror, a swoon-worthy apparition.

‘The figure of Uncle Silas rose up, with a death like scowl’ (undated), Charles Stewart, pen and ink on Whatman board, Royal Academy of Arts, London

Afterwards we caught the penultimate day of Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination at the British Library. Although a large proportion of the exhibition was in the form of books and documents I was surprised at how broad it was. 250 years of the Gothic tradition were on display and I left feeling as though I had encountered every facet of it. From Walpole’s fake historic creations to the inspired fashion of Alexander McQueen; an obsession with the dark, macabre and just plain weird still resonates today. I particularly liked the Victorian vampire slaying kit, complete with holy water, powdered garlic and wooden stakes (apparently there aren’t many of them in existence, I wonder why?).

It is amazing how a taste for the Gothic infiltrated through all levels of British culture. Edmund Burke‘s very serious treatise on the sublime for example brought a psychological view of that particular stem of Gothic, where as the posters for Hammer Horror films are in equal parts raunchy and ridiculous. The Gothic sense of humor it seems has always existed. The fascination with depicting pseudo-histories must have caused the creators great amusement. William Beckford did it with his novel Vathek, presenting it as a ‘discovered document’ as did his Gothic predecessor Walpole. An example on display here is Henry Fuseli‘s Percival Delivering Belisane from the Enchantment of Urma (first exhibited in 1783). Upon seeing this Lord Byron scoured his library for an explanation of the story, thinking it must be a scene of noble history or mythology. Failing to find anything he asked Fuseli what the story was, who freely admitted that he made it up. Although this must have been very disagreeable to his fellow Royal Academicians isn’t it a great painting? I love the expressions on the faces of Percival and Belisane, he the stereotypical chivalrous hero, she the weak and vulnerable prey. The spectral faces on the right are very strange, a supernatural blob of heads each conveying a different emotion. It must have created quite a furore exhibited in the same room as Sir Joshua Reynolds‘ regal portraits.

Percival Delivering Belisane from the Enchantment of Urma (1783) by Henry Fuseli, oil on canvas, Tate, London

These two exhibitions show exactly why the Gothic has endured; people want to be shocked and excited, to be transported to a place which triggers adrenaline and makes the heart race, whether through literature, art or film. I for one wouldn’t get a kick out of jumping out of a plane, but M. R. James’ ghost stories have physically scared me to the point where I’ve closed the book. I still get creeped out by Nosferatu, surely the scariest film ever made. The Gothic is a manifestation of taboo themes; religion, sex, race, science, and insanity to name a few, which society had and still has a morbid fascination with. Madness, asylums and those with unhinged minds could be a seen as a cause for anxiety, both unpredictable and uncontrollable, but they are nonetheless captivating. Think of Shakespeare’s Ophelia, or Emily Bronte’s Bertha, Mr Rochester’s mad wife in the attic. Nowadays the Arkham Asylum Batman graphic novels play on the same fears. The villains are always insanely evil. There are so many branches to the Gothic and I love them all, the darkness, the weirdness, the drama, the opulence and that visceral, pulse-racing thrill that unites them.

Charles Stewart, Black and White Gothic, Royal Academy of Arts is on until 15th February 2015. Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination was on at the British Library.