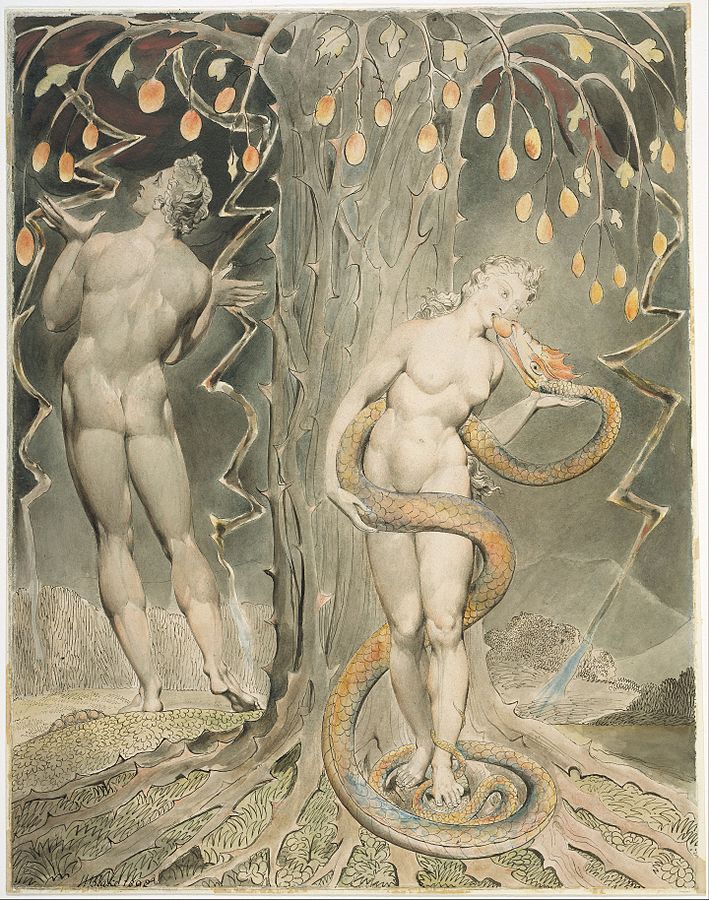

The Temptation and Fall of Eve

I finally got around to reading John Milton’s Paradise Lost, and since finishing it I have found myself thinking about it often. Comprised of 645 verses, the poem is a deeply personal and epic retelling of the Genesis story, with which Milton set out to ‘assert Eternal Providence, and justify the ways of God to men’. Considered to be the greatest English poem ever written (Samuel Johnson thought it one of the highest ‘productions of the human mind’), many artists have been inspired to translate Milton’s words into images, but it was the work of one man that came to my mind repeatedly while reading; William Blake.

Blake obviously felt an affinity with Milton. Both were poets, deeply religious, inquisitive intellectuals, actively political, and the works of both express the anxiety of the times they lived through. Perhaps above all, the two were concerned with expressing their minds, no matter how strange or radical. Blake said of Milton that ‘he was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it’, and I think that the same could be said of Blake. He definitely had a dark imagination, and had even experienced visions as a child. When it comes to envisaging the prose of Milton, I think Blake is the best man for the job.

William Blake (1757–1827) illustrated Paradise Lost more than any other artist, refining his interpretation of Milton’s words each time he revisited them. This watercolour, depicting The Temptation and the Fall of Eve (1808) is one of a set of 12 plates commissioned by Reverend Thomas Butts, one of Blake’s most loyal patrons. The so-called Butts Set (1804-1810) is the largest and more vivid of all the versions, and, I think, the most sophisticated. This is the passage that this watercolour depicts, the scene when Eve resolves to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge:

Here grows the cure of all, this fruit divine,

Fair to the eye, inviting to the taste,

Of virtue to make wise: what hinders then

To reach, and feed at once both body and mind?

So saying, her rash hand in evil hour

Forth reaching to the fruit, she plucked, she ate:

Earth felt the wound, and Nature from her seat

Sighing through all her works gave signs of woe,

That all was lost.

Book IX, 776-784

This unmistakably Blakean vision presents us with the climax of Milton’s verse, stated simply but powerfully; ‘she plucked, she ate’. Satan, in the form of a snake, ‘his head crested aloft… With burnished neck of verdant gold’, appears glossy and resplendent. He is victorious, having used cunning and flattery to convince Eve to eat from the Tree of Knowledge, of good and evil, which God had ‘pronounced it death to taste’. In the scenes leading up to this one, the serpent told her the reason he was so intelligent, beautiful and able to speak was that he had tasted of this forbidden fruit. He sways Eve into doing the same, calling her such things ‘sov’regin mistress…celestial beauty…a goddess among gods’. He finally wins her over (fairly easily, actually) by saying that the reason God had set this one rule in Paradise was to test her, and to defy Him would prove her superiority and independence, and through doing so she could be like God. In the painting, Blake has the snake feed Eve from his mouth, she literally, willingly, swallows his words.

His mental grip over Eve is strengthened physically in the way he coils himself around her body. She lifts his head up to hers and holds him to her waist in a distinctly erotic way. With her body gracefully posed in contrapposto, Eve’s beautiful face is frozen in an expression of that recognisable line between ecstasy and dread. It is at this moment that the spell is broken, she becomes ‘conscious’, a veil is lifted and realises her sin against God. Her wide eyes and open mouth are mirrored by the snake, but while he is clearly smiling she is not. The landscape also reacts to Eve’s fall, Milton said ‘Earth felt the wound’, and in the very instant when she is in alliance with Satan, Nature stirs, lightning breaks from the sky, dividing the heavens from Earth. We are trapped in the scene, confined and stifled with a sense of foreboding. The tree’s great thorny pillar of a trunk divides the composition, its drooping, heavy fruit-laden branches creating a canopy overhead. Compositionally it creates a kind of Romanesque double-arched window. To the left we see Adam from behind, his face turned towards the apocalyptic red sky. He is unaware of what Eve has done, what he is capable and willing to do for her, and the fate that awaits them both. The dividing earth and sky perhaps symbolise Man’s impending doom; to be expelled from Paradise, distanced from God and therefore to know evil and Hell.

The figures of Adam and Eve are very Michelangelesque in their musculature (Blake admired his Sistine Chapel paintings), but there is something defiantly Gothic about their interpretation. They are stiff and stony despite their ethereal lightness, separating us from them and marking them out as higher beings. The great E. H. Gombrich said that Blake ‘was the first artist after the Renaissance who thus consciously revolted against the accepted standards of tradition’, resulting in many of his contemporaries being baffled by his artistic purpose and thinking him mad. But despite living in an age of enlightenment Blake found no need for such restrictive rules as anatomy or perspective. His unique mind is the key to his art, and it gave him access to dark, mystical, fantastical concepts which were concerned with spirituality over reason or science. Milton spoke of ‘the Eye of Imagination’, something that Blake would have related to as a visionary artist, relying solely on his own creativity and realising it through his bold, uncompromising will.

Written with striking vivacity and purpose, the profound meaning of Paradise Lost is contained in the words; how they are put in sentences and built into verses, the way they feel and sound as they are read, the imagery they conjure. Blake has left an enduring visual legacy to Milton’s epic poem, which he said spoke ‘of things invisible to mortal sight.’ Although not always translated verbatim, Blake fully utilises the power embedded in colour, composition and symbolic references to get across the poem’s significance. Visual language enriches literature, adding a more instantly elemental and visceral level of understanding, and Blake exalts Milton’s words in a way that no other artist has been able to.