Art of China

July 2014 BBC2, presented by Andrew Graham-Dixon

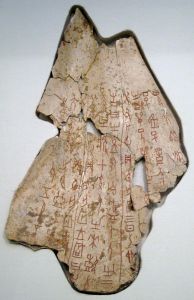

Art narrates civilisation, and such a large and ancient country as China has so much to tell us of the people and their culture. Chinese history is often thought of as a succession of dynasties, but their ancient origins are tribal. Graham-Dixon begins by looking at the ‘dragon bones’ from the Shang years of China. Dating from around 11th century BC, turtle shells and ox scapulae were inscribed with questions by the ruler’s diviner, who would ‘read’ the answers within the cracks. Aside from telling us about their beliefs and rituals, these bones are important because they bear the beginnings of Chinese language. Being pictographic in itself, written Chinese is a form of art. Think of the fluid calligraphy of brush and ink, the symbolic shapes and flourishes. The very characters have meaning other than the words they represent. There is a moral code, one of tradition and belief. The symbol for woman for example represents a figure, wide hips, crossed legs and a stick through her hair. Unmarried women could wear their hair loose, but wives had to tie it up. The language therefore became the foundation of the Chinese civilisation, to teach and to spread tradition.

Ox scapula with a divination inscription from the Shang dynasty, National Museum of China in Beijing.

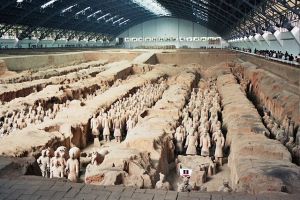

Qin Shi Huang (260–210 BC) was the first emperor of China, responsible for uniting the tribes under his rule. He was a tyrant, brutal, totalitarian. The 22 square miles of his mausoleum is his legacy, and easily outdo the Egyptian pyramids. 6.3km in circumference his burial ground is a city. This monumental project, begun by the newly crowned emperor at the age of 13, took 38 years to complete. His tomb lies under a 76 meter high mound. He even had a functioning iron chariot cast, complete with four horses to transport his spirit after his demise. However the most famous aspect of this vast necropolis is his terracotta army. Only uncovered in 1974 the 8,000 soldiers (not to mention horses and chariots) is funerary art in the extreme. Each soldier is different; they are uniquely distinct and characteristic of different parts of China. But they all march under the same emperor. And the artist? An army of 700,000 workers hand crafted each life-size sculpture. The making itself is a statement of the First Emperor’s regime. And what a statement it is. From an artistic point of view it is a colossal development.

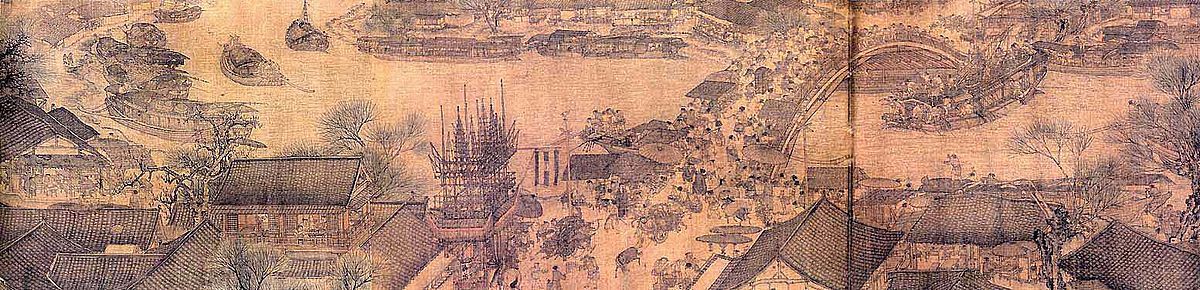

Episode two starts with the Great wall of China, the largest man-made structure and one of the seven wonders of the world. It signifies imperial power, but also an insecurity and preparation of threat from outsiders. Despite the defenses ideas infiltrated into China. The Silk Road linked the East with the West, passing through Arabia, Persia and India. It meant trade but also the exchange of beliefs and customs. From India came Buddhism. Buddhist monks made caves along the route, providing a welcome alternative to the strict Daoism religion enforced by rulers. The Tang dynasty took up Buddhism, bringing freedom, enlightenment, and acceptance. Art in the form of wall paintings portray the Chinese people, their actions. The observation of nature can also be seen in art of this period, a subject which became an enduring source of inspiration for Chinese artist. It could be synonymous with beauty, purity and order, but also violence, unpredictability and the sublime. Scroll paintings show vast mountain ranges, forests of indigenous trees, sometimes a dwarfed figure or animal to further exaggerate the awe-inspiring enormity of nature. The tradition of scroll painting developed significantly during the Song dynasty (960-1279) with ceremonious celebratory artworks. Zhang Zeduan‘s Along the River During the Qingming Festival is over 25 meters long and captures the hustle and bustle of the capital city. It shows the population, from people pushing carts and selling wares to wealthy men being carried in sedan chairs. Overall it is a celebration of society, one of industry, prosperity, and harmonious hierarchy. But beyond this is the artistic observation of character. In the detail shown below a boat with its sails not fully lowered sails towards a bridge. The men on board frantically work to get them down in time, while onlookers on the bridge panic. After the cryptic ‘dragon bones’ and formidable terracotta army art of this shows acute human emotion of an ordinary kind. As Graham-Dixon points out, Hogarth would have approved.

Detail of Along the River During the Qingming Festival (1085-1145) by Zhang Zeduan, Palace Museum, Beijing

Detail from Nine Dragons (1244) by Chen Rong, ink and colour on Xuan paper, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The 12th century saw the invasion of China by Genghis Khan and the fall of the Song court in 127. Chen Rong’s Nine Dragons gives an idea of the fear and uncertainty of the time. Painted around 1244, this is one of the greatest artworks in Chinese history. 10 meters in length it shows nature as a danger, the weather threatens, the dragons loom in the darkness. It is symbolic of the Mongol attack, and the new reign of Kublai Khan in the new capital of Beijing. Although seen as barbarians and being nomads at heart, the art that came from this Mongol dynasty was to prove to be one of extreme creativity. The old scholars and intellectuals of the Song dynasty left the city to and retreated to the mountains. One such man was Ni Zan who devoted himself to painting and poetry. Six Gentlemen is one of the literati masterpieces. Six pine trees are elusive, but the image as a whole is emotive and expressive. He painted this image many times. The accompanying calligraphy is art in itself. The little brushstrokes, like that of the calligraphy are delicate, fragile and impulsive. He said ‘“I use bamboo painting to write out the exhilaration in my breast, that is all. Why should I worry whether it shows likeness or not?”. This is something radically new; artists creating art for themselves, depicting what they want and how they want to.

The first art of China preoccupied with death and the afterlife. Then came the fascination with the living, scholarly learning, sublime nature and god-like emperors. The last imperial dynasty of China was that of the Qing, they were foreigners from Manchuria and where as their Ming predecessors were introvert, the art of their rule shows a different attitude. It is significant that the greatest artist from this period was not Chinese. Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) was an Italian missionary, who had come to China with the Jesuit order. He became Emperor Qianlong’s favourite painter, and brought something revolutionary the country’s art; perspective. Of course this was nothing new to Europe, but Chinese painting had always been flat and linear. There was none of the European obsession with mathematical precision and dimension in painting. Castiglione’s work for the court was a perfect blend of glorifying Chinese subject matter with Western techniques of realism. The Qianlong Emperor in Ceremonial Armour on Horseback (1758) shows shows this hybrid perfectly. It is the first of its kind in the East, the tradition of equestrian portraiture was of European origin, but the image is quintessentially Chinese. The artist captures the Emperor as a mighty ruler; a warrior, a hunter and protector. The background is sensitive to the great reverence of the landscape in Chinese art, and is scroll-like in its delicate treatment. The emperor and his horse are bold, colourful and have weight. There seems to be a reluctance to depict the perspective and light that reality brings, not wanting to fully unleash the Western influence. They don’t quite look convincing. But it is groundbreaking nonetheless. There is also a change in format for purposes of display, and so paintings of this kind would be more convenient than scrolls.

The Qianlong Emperor in Ceremonial Armour on Horseback (1758) by Giuseppe Castiglione, ink and colour on silk, Palace Museum, Beijing

Today Chinese artists seek a medium that all at once hearkens back to tradition, deals with the present and finds a national identity. Art is both inward and outward looking, contemplative and reactionary. Andrew Graham-Dixon tells the story of Chinese art as an evolutionary process, through the history of the people and development of society. I personally find Chinese history quite overwhelming because of its complexity. But in fact analysing it through it’s art and culture makes things relatable and understandable. An enlightening series.