Anarchy & Beauty: William Morris and His Legacy 1860-1960

Amid the modern and industrious Victorian age William Morris (1834-1896) was a man who strove to revive the tradition the lost traditions of craftsmanship and, very importantly, advocate a fair work ethic. He believed that a happy, well-paid worker would create the most masterly and inspired things of his trade. Of course Morris is most renown for his company which created patterns for wallpapers and fabrics which still prove popular today. I myself dream of a Pimpernel clad drawing room. But there is so much more to Morris than his decorative patterns. This fabulous exhibition shows us his pure visionary genius and his surprisingly anarchic spirit which endures to this day.

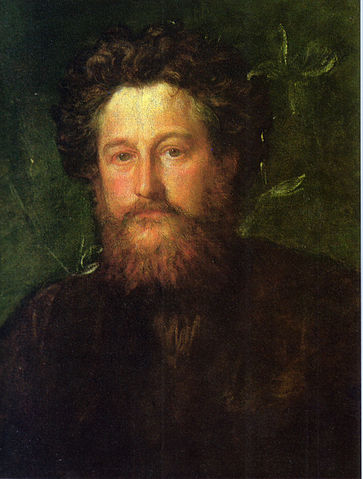

We are introduced to William Morris in the first room through portraits and possessions. A portrait by the artist G. F. Watts depicts the sitter as a man of intelligence and energy. He has a honest and open expression. His leonine mane of curly hair and bushy beard give him the look of a natural creative and romantic. Which indeed he was. He was a designer, craftsman, interior decorator, writer, political activist, environmentalist and social campaigner. By the age of 36 when this was painted Morris had accomplished a lot. As well as the establishment of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. (1861–1875) he campaigned incessantly throughout his life; he believed in equality, actively supported women’s suffrage, and dreamed of a classless world where education was for everyone and not just the privileged. His copy of Thomas More’s Utopia is on display here, a book that must have been a kind of bible for Morris . He would later lecture from it, campaign for its values and even illustrate it. Morris’ own great written work News from Nowhere (1890) maintained More’s social principles and optimism for the future, and had an international influence. He would later become a devotee of Marx and Engles.

As a young man Morris had been absorbed into the Pre-Raphaelite circle, although was never recognised as a fully-fledged member. In fact despite having professional relationships with some of the movement’s founders his notoriously fiery personality caused frequent squabbles. But for the main part he agreed with their medieval inspired aesthetic and revolutionary views on art. Another link to the PRB was his wife, Jane Burden (1839 – 1914) whom he married in 1859. Two years earlier her natural beauty had been spotted by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, and she quickly became their favourite muse. She sat for Morris in the only painting he ever did, La Belle Isuelt (1858), during which time the two became engaged. It was said that Jane was not in love with Morris, and in 1865 her friendship with Rossetti developed into an long love affair. Morris knew of this betrayal but endured it. In a very telling quote by Morris he said of Rossetti that he had ‘some of the very greatest qualities of genius, most of them indeed. What a great man he would have been but for the arrogant misanthropy which marred his work’. Despite his personal views on the man, his painterly style owes much to Rossetti in the rather flat surfaces and textures, the inspiration from Arthurian legend and the use of a melancholy beauty at the centre.

I think it is fair to say that his one and only painting isn’t a masterpiece. Morris had trained as an architect, so it is not surprising that he fell to more practical design. In 1860 he completed his first architectural masterpiece the Red House, co-built with architect Philip Webb. It is a monument to Morris’ Arts & Crafts aesthetic and moral values. Unlike other great Victorian buildings there is a rural vernacular to the facade, one which has a modest and informal character to it. This was William and Jane’s home for many years, a place where Morris could ‘meet with people with whom I sympathise, whom I love’. It was a haven for the Morris’, their family and friends. Relationships between the building and it’s inhabitants extended into the interior, Morris ‘clothed the house’ inside and out with emblems, allegory and pattern in all materials. And it was very much a collaborative effort, Edward Burne-Jones for example created the beautiful stained glass windows and murals. The spirit of camaraderie gave birth to Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. when Morris went into business with six other men, Webb, Burne-Jones, Rossetti and Ford Maddox Brown among them. ‘The firm’ as they called it was a great success both in England and overseas, but more importantly it became part of a bigger picture. Other furnishing and decorative arts companies sprung up with similar aims. There was more to it than aesthetics, it promoted a preference to a set of values.

The Red House in Upton, Bexleyheath, Greater London (completed 1860), Philip Webb and William Morris

Morris advocated the importance of encouraging a workforce to improve their techniques, to be artisans, to enjoy their work and so to create things which reflected their contentment. This hearkens back to the pre-Industrial Revolution age, a time when enjoyment and value of work still existed. Morris himself was anti-parliament/anti-establishment/anti-bourgeois. As mentioned above he was fan of Marx. He especially agreed with the ideas put forward in his Le Capital, an analysis of the political economy, which stood defiantly against the exploitative modes of production and the oppression of the working classes. Beauty is the common theme of Morris’ artistic work, specifically derived from nature, his constant inspiration. He believed that beauty had the power to change lives. “Beauty” he said “which is what is meant by art, using the word in its widest sense, is, I contend, no mere accident to human life, which people can take or leave as they choose, but a positive necessity of life”. This is the stuff of Ruskin, who believed that the diligent study of nature would result in art as an antidote to the moral and social decline of the times.

In a time when moral consciousness of this kind was rare, when the class boundaries seemed concrete, Morris stood for social responsibility, satisfaction of labour and quality of life. This ethic was carried forward by the whole Arts & Crafts movement, and continued to have an impact centuries after his death. In short he envisaged a return to a way of life not uncommon to that of the Middle Ages, like the PRB. His spirit of discontent at the state of England was contagious, and anarchic at times. In his wake public figures such as the formidable Octavia Hill (she petitioned for housing reform and public recreational areas) came to light. Like Morris she sought to reconcile the English rural idyll with urban industry, and campaigned for the conservation of buildings and places of importance. Likewise the post-war era saw the emergence of the Garden City and the Festival of Britain, bringing a re-birth of national pride, energy and ethical industry. The second half of this exhibition shows how through cultural icons such as Robin and Lucienne Day, Terence Conran and Heal & Son Ltd Morris’s legacy lives on today. Out of all of the things that he sought to improve, humanity was at the core of his work. He revolutionised everything he touched. Upon his death his doctor said that he ‘died of being William Morris and having done more work than most ten men’. Surely there there is no greater testament than that.